16.2: Preparation of alkylbenzenes

- Page ID

- 225869

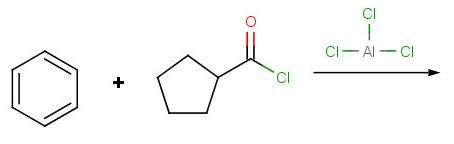

Friedel-Crafts reactions

Compounds containing aromatic groups are widespread in nature, and for this reason chemists who aim to synthesize naturally occurring compounds in the laboratory often need to introduce substituents to aromatic rings. In the organic synthesis laboratory, electrophilic aromatic substitutions which result in the formation of new carbon-carbon bonds are called ‘Friedel-Crafts’ alkylations and acylations, named for Charles Friedel of France and James Crafts of the United States, who together developed the procedures in 1877. The Friedel-Crafts reactions are an important part of a synthetic chemist’s toolbox to this day.

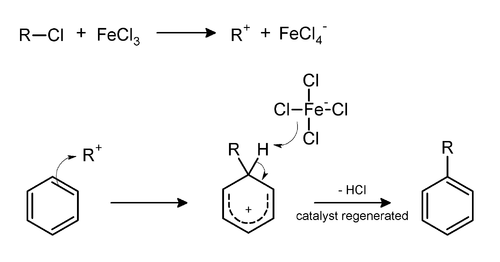

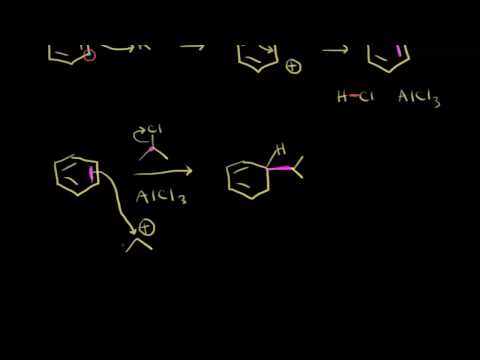

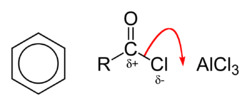

Friedel Crafts reactions, like their biochemical counterparts, require reactive electrophiles with significant carbocation character. One of the most common ways to alkylate an aromatic ring is to use an alkyl chloride electrophile that is activated by the addition of aluminum or iron trichloride. The metal chloride serves as a Lewis acid, accepting electron density from the alkyl chloride. This has the effect of magnifying the carbon-chlorine dipole, making the carbon end more electropositive – and thus more electrophilic – even to the point where the bond breaks and an ion-pair is formed.

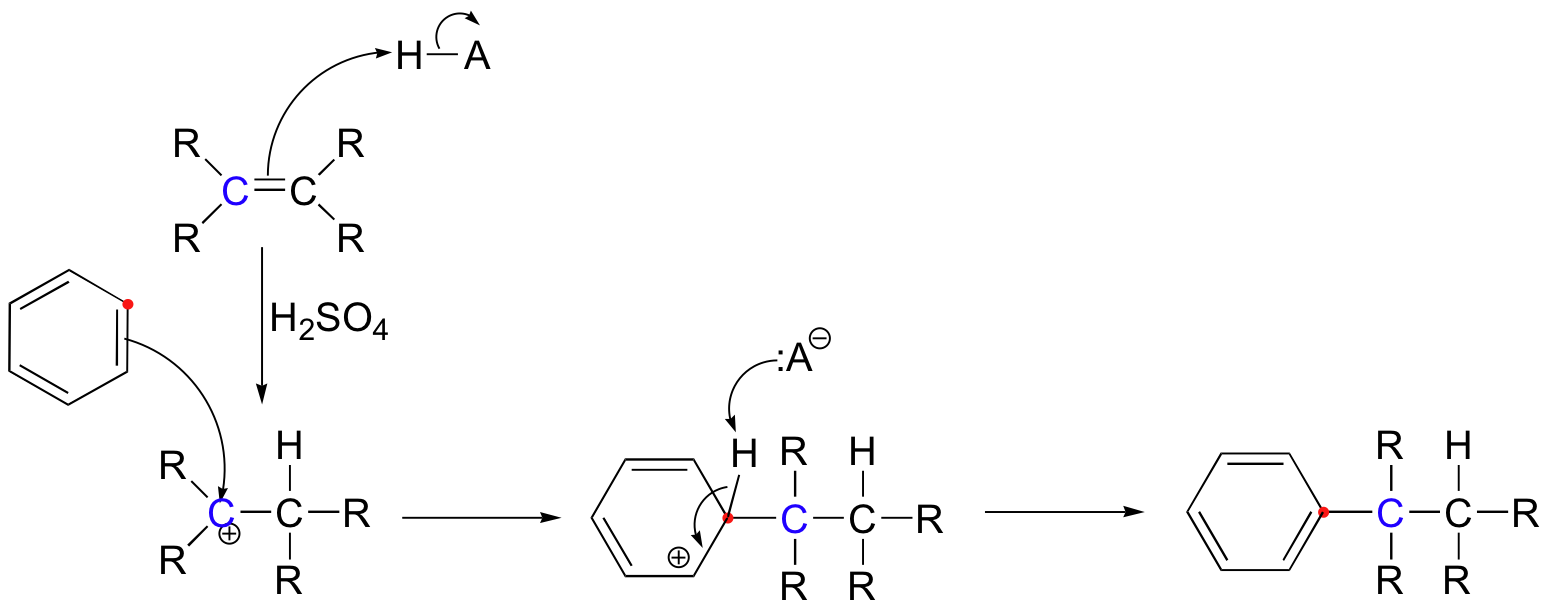

An alternative method for carrying out a Friedel-Crafts alkylation is to start with an alkene, which is protonated by a strong acid such as H2SO4 to generate a carbocation.

Limitations of Friedel-Crafts Alkylation

- Carbocation Rearrangement – Only certain alkylbenzenes can be made due to the tendency of cations to rearrange.

- Compound Limitations – Friedel-Crafts fails when used with compounds such as nitrobenzene and other strongly deactivated aromatics.

- Polyalkylation – Products of Friedel-Crafts alkylations are even more reactive than starting material. Alkyl groups produced in Friedel-Crafts Alkylation are electron-donating substituents meaning that the products are more susceptible to electrophilic attack than what we began with. For synthetic purposes, this is a big disappointment, because the reaction is hard to stop with just a single alkylation.

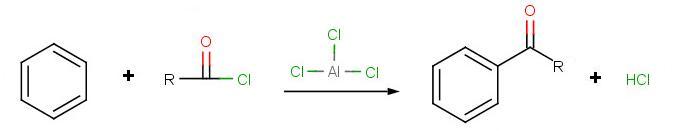

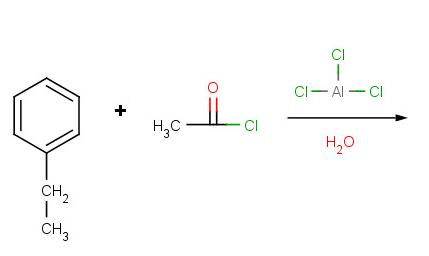

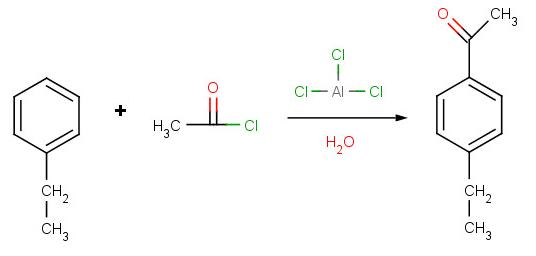

To remedy some of these limitations (1 and 3), Friedel-Crafts acylation is often used instead, followed by reduction of the ketone product.

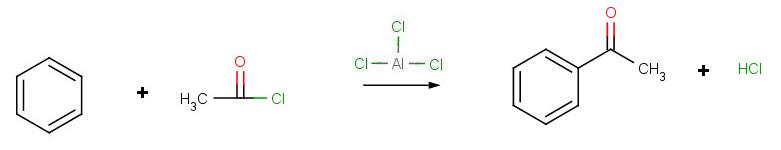

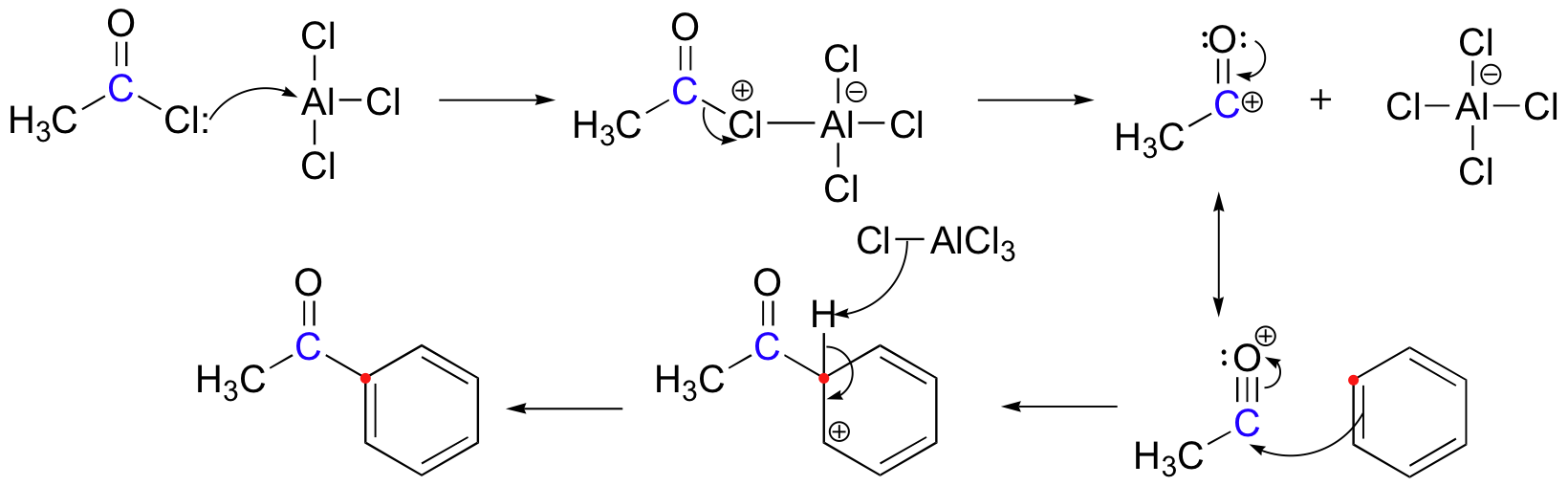

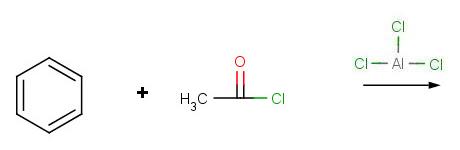

The Friedel-Crafts acylation reaction is essentially an acyl substitution (chapter 22) reaction with an aromatic π bond serving as the nucleophile. As in many other laboratory acyl transfer reactions, acyl chlorides are used as activated carboxylic acids. Because of the low reactivity of the aromatic π bond nucleophile, however, the acyl chloride electrophile in a Friedel-Crafts acylation must be further activated with a Lewis acid reagent such as aluminum chloride, which again serves to polarize the carbon-chlorine bond and increase the electrophilicity of the acyl carbon. The activated electrophile in Friedel-Crafts acylations is often depicted as an ionic species.

The resultant aryl ketone can be reduced to CH3CH2Ph (ethylbenzene) using H2/Pd on C, or Zn(Hg) and HCl, as described in the latter part of section 14.2.

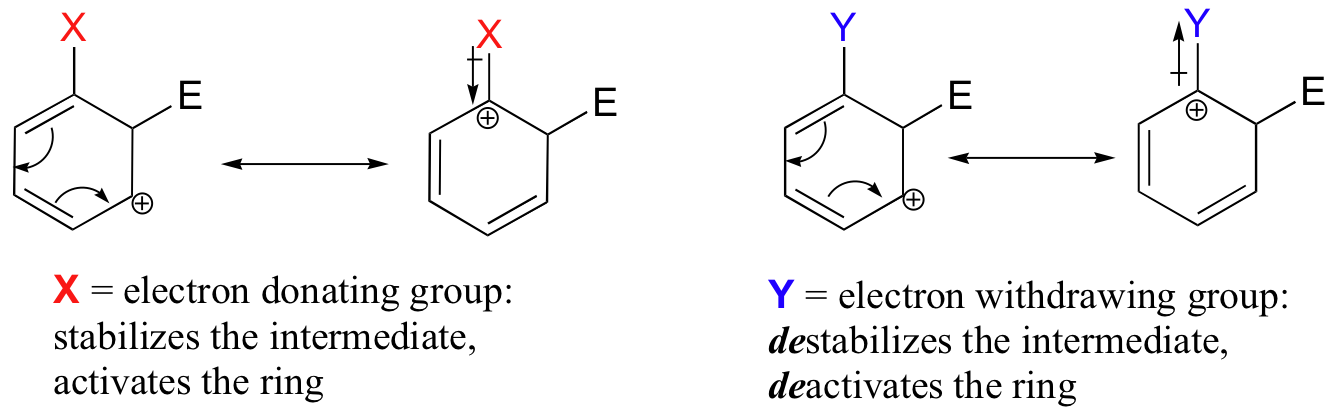

Substituent effects in Friedel-Crafts reactions

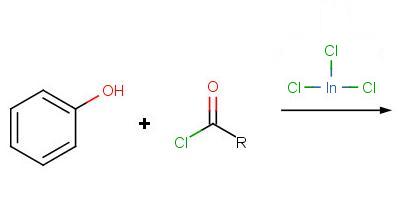

The reactivity of aromatic pi bonds in SEAr reactions is very sensitive to the presence of electron-donating groups (EDG) and electron-withdrawing groups (EWG) on the aromatic ring. This is due to the carbocation nature of the intermediate, which is stabilized by electron-donating groups and destabilized by electron-withdrawing groups. As a rule, both the acylation and alkylation Friedel-Crafts reactions fail when meta-directing deactivators are present. Thus nitrobenzene (a deactivated ring) fails to react in the Friedel-Crafts reaction. However the reaction is successful with halogen substituents are present, as in chlorobenzene.

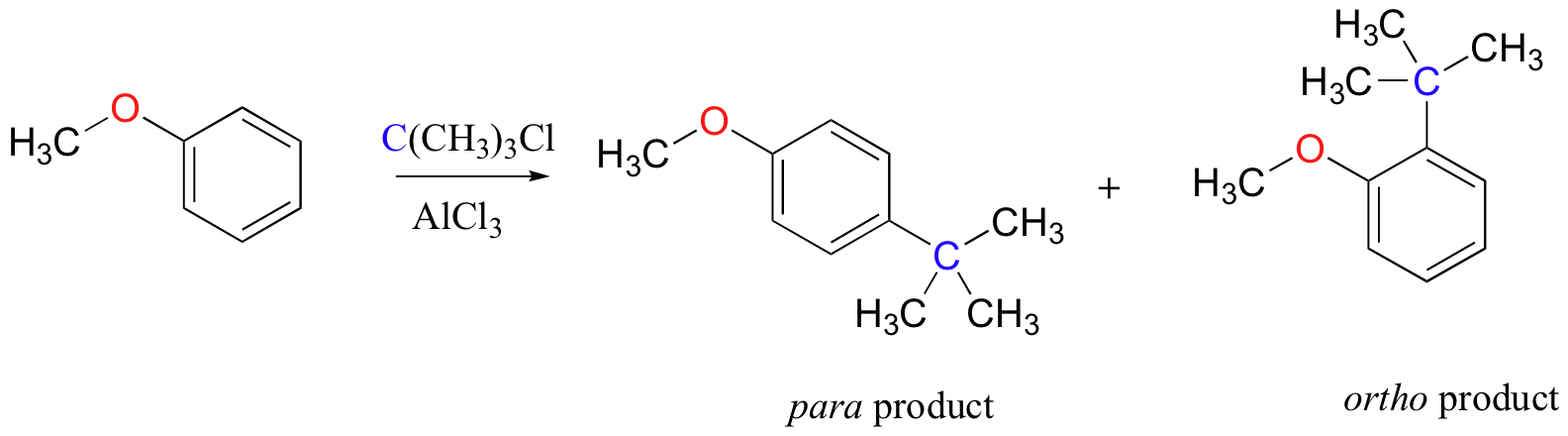

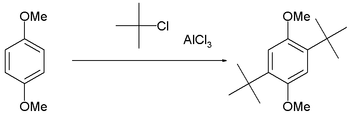

The Friedel-Crafts alkylation of methoxy benzene would be expected to produce a mixture of the ortho and para substituted products, but no meta-substituted product.

In addition, the para product would be expected to be preferred over the ortho product, due to steric and inductive considerations.

Contributors

- Organic Chemistry With a Biological Emphasis by Tim Soderberg (University of Minnesota, Morris)

Friedel-Crafts Acylation

Limitations of Friedel-Crafts Alkylation

- Carbocation Rearrangement – Only certain alkylbenzenes can be made due to the tendency of cations to rearrange.

- Compound Limitations – Friedel-Crafts fails when used with compounds such as nitrobenzene and other strong deactivating systems.

- Polyalkylation – Products of Friedel-Crafts are even more reactive than starting material. Alkyl groups produced in Friedel-Crafts Alkylation are electron-donating substituents meaning that the products are more susceptible to electrophilic attack than what we began with. For synthetic purposes, this is a big disappointment.

To remedy these limitations, a new and improved reaction was devised: The Friedel-Crafts Acylation, also known as Friedel-Crafts Alkanoylation.

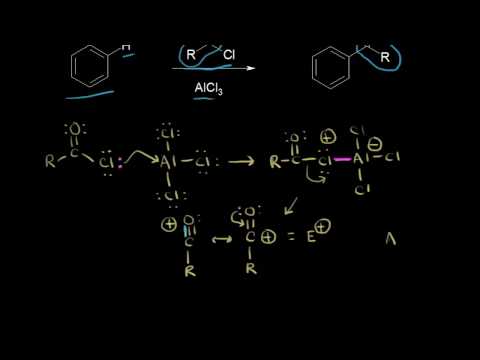

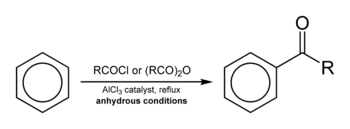

The goal of the reaction is the following:

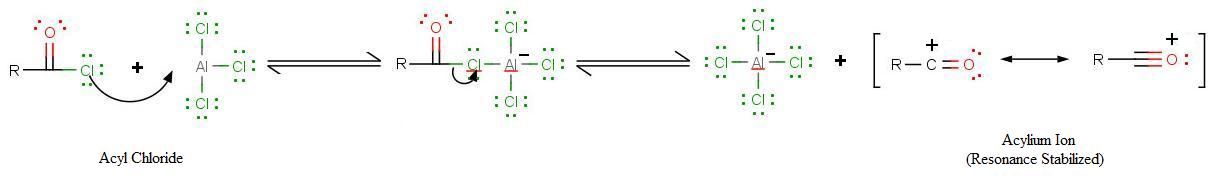

The very first step involves the formation of the acylium ion which will later react with benzene:

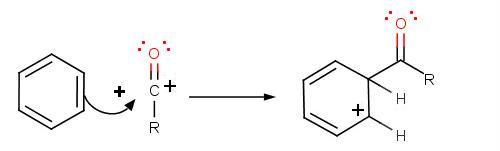

The second step involves the attack of the acylium ion on benzene as a new electrophile to form one complex:

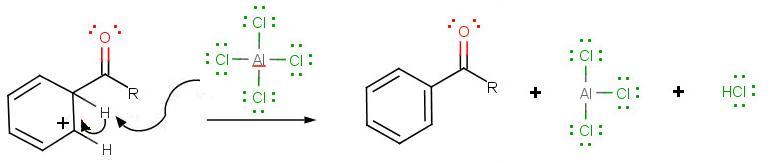

The third step involves the departure of the proton in order for aromaticity to return to benzene:

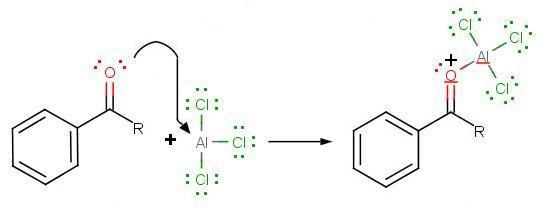

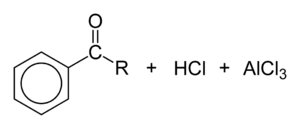

During the third step, AlCl4 returns to remove a proton from the benzene ring, which enables the ring to return to aromaticity. In doing so, the original AlCl3 is regenerated for use again, along with HCl. Most importantly, we have the first part of the final product of the reaction, which is a ketone. The first part of the product is the complex with aluminum chloride as shown:

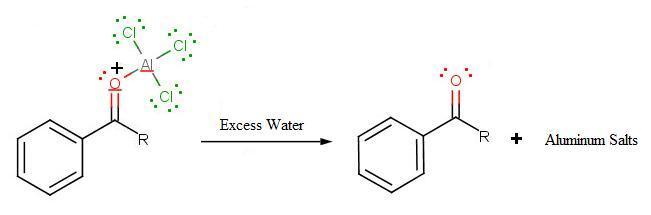

The final step involves the addition of water to liberate the final product as the acylbenzene:

Because the acylium ion (as was shown in step one) is stabilized by resonance, no rearrangement occurs (Limitation 1). Also, because of of the deactivation of the product, it is no longer susceptible to electrophilic attack and hence, is no longer susceptible to electrophilic attack and hence, no longer goes into further reactions (Limitation 3). However, as not all is perfect, Limitation 2 still prevails where Friedel-Crafts Acylation fails with strong deactivating rings.

References

- Vollhardt, and Schore. Organic Chemistry Sturcture and Function. 5th ed. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 2007.

- Wade Jr., L.G. Organic Chemistry. 6th ed. New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006.

Problems

Problem 1:

Problem 2:

Problem 3:

Problem 4:

Problem 5:

Solutions

Solution to Problem 2:

Solution to Problem 3:

Solution to Problem 4:

Solution to Problem 5:

Contributors

- Mario Morataya (UCD)

Friedel–Crafts reaction

Friedel–Crafts alkylation

Friedel–Crafts alkylation involves the alkylation of an aromatic ring with an alkyl halide using a strong Lewis acid catalyst.[6] With anhydrous ferric chloride as a catalyst, the alkyl group attaches at the former site of the chloride ion. The general mechanism is shown below.

This reaction suffers from the disadvantage that the product is more nucleophilic than the reactant. Consequently, overalkylation occurs. Furthermore, the reaction is only very useful for tertiary alkylating agents, some secondary alkylating agents, or ones that yield stabilized carbocations (e.g., benzylic ones). In the case of primary alkyl halides, the incipient carbocation (R(+)—X—Al(-)Cl3) will undergo a carbocationrearrangement reaction.

Steric hindrance can be exploited to limit the number of alkylations, as in the t-butylation of 1,4-dimethoxybenzene.

Alkylations are not limited to alkyl halides: Friedel–Crafts reactions are possible with any carbocationic intermediate such as those derived from alkenes and a protic acid, Lewis acid, enones, and epoxides. An example is the synthesis of neophyl chloride from benzene and methallyl chloride:

- H2C=C(CH3)CH2Cl + C6H6 → C6H5C(CH3)2CH2Cl

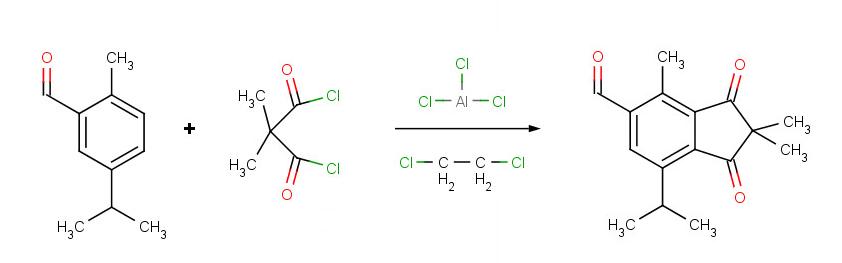

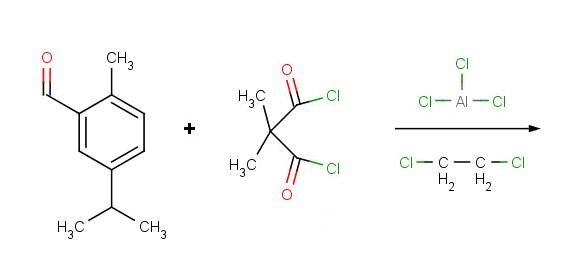

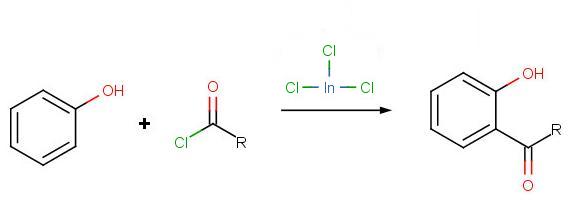

Friedel–Crafts acylation

Friedel–Crafts acylation involves the acylation of aromatic rings. Typical acylating agents are acyl chlorides. Typical Lewis acid catalysts are acids and aluminium trichloride. Friedel–Crafts acylation is also possible with acid anhydrides.[11] Reaction conditions are similar to the Friedel–Crafts alkylation. This reaction has several advantages over the alkylation reaction. Due to the electron-withdrawing effect of the carbonyl group, the ketone product is always less reactive than the original molecule, so multiple acylations do not occur. Also, there are no carbocation rearrangements, as the acylium ion is stabilized by a resonance structure in which the positive charge is on the oxygen.

The viability of the Friedel–Crafts acylation depends on the stability of the acyl chloride reagent. Formyl chloride, for example, is too unstable to be isolated. Thus, synthesis of benzaldehyde through the Friedel–Crafts pathway requires that formyl chloride be synthesized in situ. This is accomplished by the Gattermann-Koch reaction, accomplished by treating benzene with carbon monoxide and hydrogen chloride under high pressure, catalyzed by a mixture of aluminium chloride and cuprous chloride.

Reaction mechanism

The reaction proceeds through generation of an acylium center:

The reaction is completed by deprotonation of the arenium ion by AlCl4−, regenerating the AlCl3 catalyst:

If desired, the resulting ketone can be subsequently reduced to the corresponding alkane substituent by either Wolff–Kishner reduction or Clemmensen reduction. The net result is the same as the Friedel–Crafts alkylation except that rearrangement is not possible.

- 15.6: Synthetic parallel - electrophilic aromatic substitution in the lab. Authored by: Tim Soderberg. Provided by: University of Minnesota, Morris. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Book%3A_Organic_Chemistry_with_a_Biological_Emphasis_(Soderberg)/15%3A_Electrophilic_reactions/15.06%3A_Synthetic_parallel_-_electrophilic_aromatic_substitution_in_the_lab. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts . License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Friedel-Crafts Acylation. Authored by: Mario Morataya. Provided by: UCD. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Supplemental_Modules_(Organic_Chemistry)/Arenes/Reactivity_of_Arenes/Friedel-Crafts_Acylation. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Friedelu2013Crafts reaction. Authored by: Wikipedia. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friedel%E2%80%93Crafts_reaction. Project: Wikipedia. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 18.10: Limitations on Electrophilic Substitution Reactions with Substituted Benzenes. Authored by: William Reusch, Professor Emeritus; Prof. Steven Farmer. Provided by: Michigan State U; Sonoma State University. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/Textbook_Maps/Organic_Chemistry/Map%3A_Organic_Chemistry_(Smith)/Chapter_18%3A_Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution/18.10%3A_Limitations_on_Electrophilic_Substitution_Reactions_with_Substituted_Benzenes. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 16.10 Reduction of Aromatic Compounds. Authored by: Dr. Dietmar Kennepohl FCIC; Prof. Steven Farmer; William Reusch, Professor Emeritus; Mario Morataya; Gamini Gunawardena . Provided by: Athabasca University; Sonoma State University; Michigan State U; UCD; Utah Valley University. Located at: https://chem.libretexts.org/LibreTexts/Athabasca_University/Chemistry_350%3A_Organic_Chemistry_I/Chapter_16%3A_Chemistry_of_Benzene%3A_Electrophilic_Aromatic_Substitution/16.10_Reduction_of_Aromatic_Compounds. Project: Chemistry LibreTexts. License: Public Domain: No Known Copyright