3.7: Corrosion

- Page ID

- 206933

Corrosion is a galvanic process by which metals deteriorate through oxidation—usually but not always to their oxides. For example, when exposed to air, iron rusts, silver tarnishes, and copper and brass acquire a bluish-green surface called a patina. Of the various metals subject to corrosion, iron is by far the most important commercially. An estimated $100 billion per year is spent in the United States alone to replace iron-containing objects destroyed by corrosion. Consequently, the development of methods for protecting metal surfaces from corrosion constitutes a very active area of industrial research. In this section, we describe some of the chemical and electrochemical processes responsible for corrosion. We also examine the chemical basis for some common methods for preventing corrosion and treating corroded metals.

Corrosion is a REDOX process.

Under ambient conditions, the oxidation of most metals is thermodynamically spontaneous, with the notable exception of gold and platinum. Hence it is actually somewhat surprising that any metals are useful at all in Earth’s moist, oxygen-rich atmosphere. Some metals, however, are resistant to corrosion for kinetic reasons. For example, aluminum in soft-drink cans and airplanes is protected by a thin coating of metal oxide that forms on the surface of the metal and acts as an impenetrable barrier that prevents further destruction. Aluminum cans also have a thin plastic layer to prevent reaction of the oxide with acid in the soft drink. Chromium, magnesium, and nickel also form protective oxide films. Stainless steels are remarkably resistant to corrosion because they usually contain a significant proportion of chromium, nickel, or both.

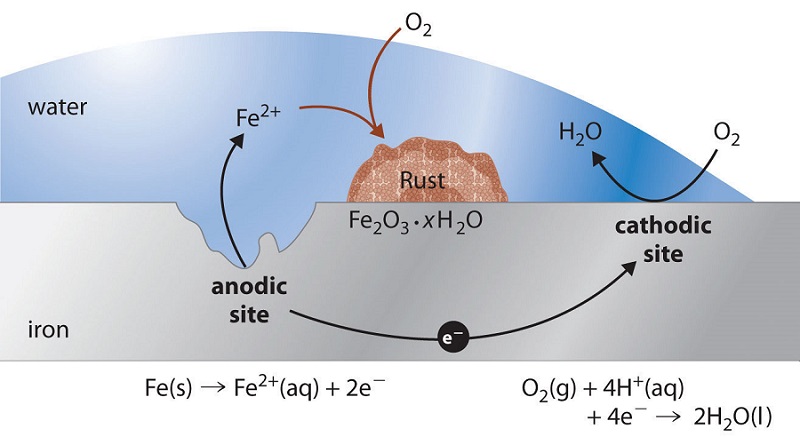

In contrast to these metals, when iron corrodes, it forms a red-brown hydrated metal oxide (Fe2O3•xH2O), commonly known as rust, that does not provide a tight protective film (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). Instead, the rust continually flakes off to expose a fresh metal surface vulnerable to reaction with oxygen and water. Because both oxygen and water are required for rust to form, an iron nail immersed in deoxygenated water will not rust—even over a period of several weeks. Similarly, a nail immersed in an organic solvent such as kerosene or mineral oil saturated with oxygen will not rust because of the absence of water.

In the corrosion process, iron metal acts as the anode in a galvanic cell and is oxidized to Fe2+; oxygen is reduced to water at the cathode. The relevant reactions are as follows:

- at cathode: \[O_{2(g)} + 4H^+_{(aq)} + 4e^− \rightarrow 2H_2O_{(l)} \;\;\; E°=1.23\; V \label{Eq1}\]

- at anode: \[Fe{(s)} \rightarrow Fe^{2+}_{(aq)} + 2e^−\;\;\; E° = −0.45\; V \label{Eq2}\]

- overall: \[2Fe_{(s)} + O_{2(g)} + 4H^+_{(aq)} \rightarrow 2Fe^{2+}_{(aq)} + 2H_2O_{(l)}\;\;\; E° = 1.68\; V \label{Eq3}\]

The Fe2+ ions produced in the initial reaction are then oxidized by atmospheric oxygen to produce the insoluble hydrated oxide containing Fe3+, as represented in the following equation:

\[4Fe^{2+}_{(aq)} + O_{2(g)} + (2 + 4x)H_2O \rightarrow 2Fe_2O_3 \cdot xH_2O + 4H^+_{(aq)} \label{Eq4}\]

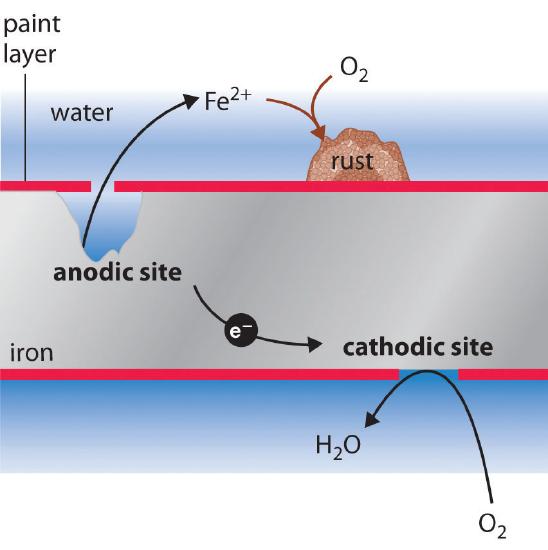

The sign and magnitude of E° for the corrosion process (Equation \(\ref{Eq3}\)) indicate that there is a strong driving force for the oxidation of iron by O2 under standard conditions (1 M H+). Under neutral conditions, the driving force is somewhat less but still appreciable (E = 1.25 V at pH 7.0). Normally, the reaction of atmospheric CO2 with water to form H+ and HCO3− provides a low enough pH to enhance the reaction rate, as does acid rain. Automobile manufacturers spend a great deal of time and money developing paints that adhere tightly to the car’s metal surface to prevent oxygenated water, acid, and salt from coming into contact with the underlying metal. Unfortunately, even the best paint is subject to scratching or denting, and the electrochemical nature of the corrosion process means that two scratches relatively remote from each other can operate together as anode and cathode, leading to sudden mechanical failure (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)).

Prophylactic Protection

One of the most common techniques used to prevent the corrosion of iron is applying a protective coating of another metal that is more difficult to oxidize. Faucets and some external parts of automobiles, for example, are often coated with a thin layer of chromium using an electrolytic process. With the increased use of polymeric materials in cars, however, the use of chrome-plated steel has diminished in recent years. Similarly, the “tin cans” that hold soups and other foods are actually made of steel coated with a thin layer of tin. Neither chromium nor tin is intrinsically resistant to corrosion, but both form protective oxide coatings.

As with a protective paint, scratching a protective metal coating will allow corrosion to occur. In this case, however, the presence of the second metal can actually increase the rate of corrosion. The values of the standard electrode potentials for Sn2+ (E° = −0.14 V) and Fe2+ (E° = −0.45 V) in Table P2 show that Fe is more easily oxidized than Sn. As a result, the more corrosion-resistant metal (in this case, tin) accelerates the corrosion of iron by acting as the cathode and providing a large surface area for the reduction of oxygen (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). This process is seen in some older homes where copper and iron pipes have been directly connected to each other. The less easily oxidized copper acts as the cathode, causing iron to dissolve rapidly near the connection and occasionally resulting in a catastrophic plumbing failure.

Cathodic Protection

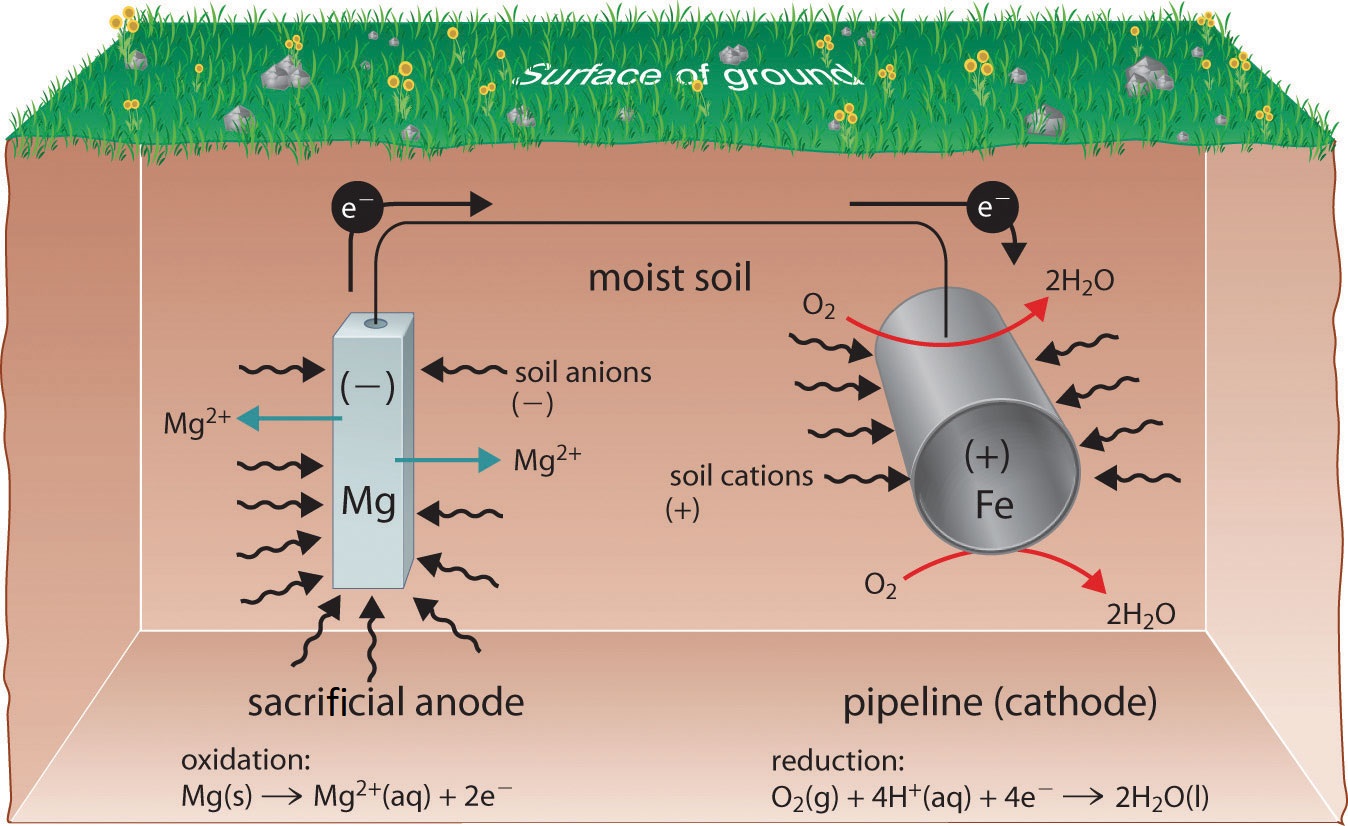

One way to avoid these problems is to use a more easily oxidized metal to protect iron from corrosion. In this approach, called cathodic protection, a more reactive metal such as Zn (E° = −0.76 V for Zn2+ + 2e−→ Zn) becomes the anode, and iron becomes the cathode. This prevents oxidation of the iron and protects the iron object from corrosion. The reactions that occur under these conditions are as follows:

\[ \underbrace{O_{2(g)} + 4e^− + 4H^+_{(aq)} \rightarrow 2H_2O_{(l)} }_{\text{reduction at cathode}}\label{Eq5}\]

\[ \underbrace{Zn_{(s)} \rightarrow Zn^{2+}_{(aq)} + 2e^−}_{\text{oxidation at anode}} \label{Eq6}\]

The more reactive metal reacts with oxygen and will eventually dissolve, “sacrificing” itself to protect the iron object. Cathodic protection is the principle underlying galvanized steel, which is steel protected by a thin layer of zinc. Galvanized steel is used in objects ranging from nails to garbage cans.

In a similar strategy, sacrificial electrodes using magnesium, for example, are used to protect underground tanks or pipes (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). Replacing the sacrificial electrodes is more cost-effective than replacing the iron objects they are protecting.

Summary

Corrosion is a galvanic process that can be prevented using cathodic protection. The deterioration of metals through oxidation is a galvanic process called corrosion. Protective coatings consist of a second metal that is more difficult to oxidize than the metal being protected. Alternatively, a more easily oxidized metal can be applied to a metal surface, thus providing cathodic protection of the surface. A thin layer of zinc protects galvanized steel. Sacrificial electrodes can also be attached to an object to protect it.