3.6.0.0: Surface Tension, Viscosity, and Capillary Action (Problems)

- Page ID

- 210724

PROBLEM \(\PageIndex{1}\)

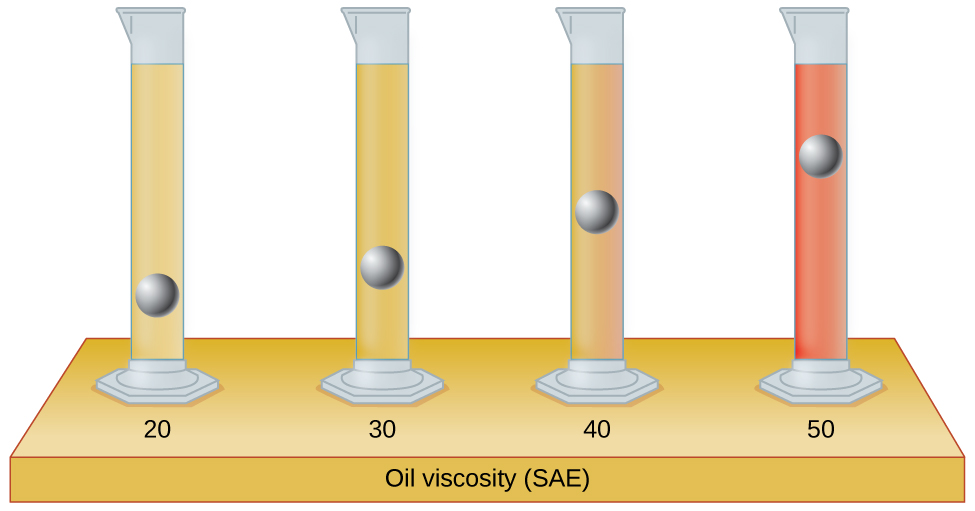

The test tubes shown here contain equal amounts of the specified motor oils. Identical metal spheres were dropped at the same time into each of the tubes, and a brief moment later, the spheres had fallen to the heights indicated in the illustration. Rank the motor oils in order of increasing viscosity, and explain your reasoning:

- Answer

-

20 < 30 < 40 < 50

PROBLEM \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Although steel is denser than water, a steel needle or paper clip placed carefully lengthwise on the surface of still water can be made to float. Explain at a molecular level how this is possible:

(credit: Cory Zanker)

- Answer

-

The water molecules have strong intermolecular forces of hydrogen bonding. The water molecules are thus attracted strongly to one another and exhibit a relatively large surface tension, forming a type of “skin” at its surface. This skin can support a bug or paper clip if gently placed on the water.

PROBLEM \(\PageIndex{3}\)

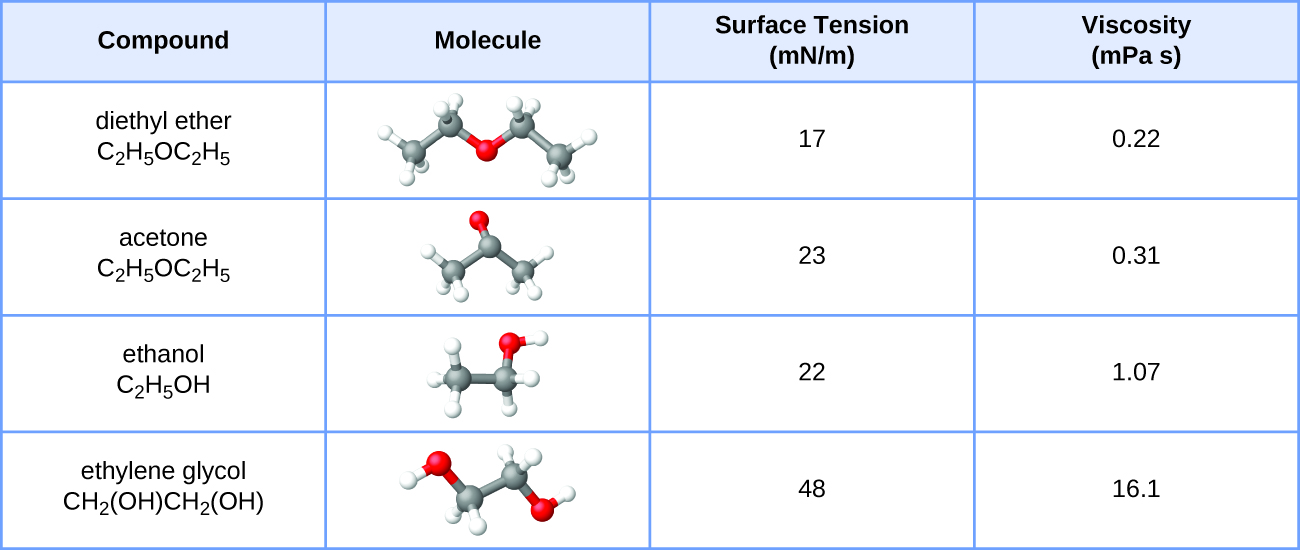

The surface tension and viscosity values for diethyl ether, acetone, ethanol, and ethylene glycol are shown here.

- Explain their differences in viscosity in terms of the size and shape of their molecules and their IMFs.

- Explain their differences in surface tension in terms of the size and shape of their molecules and their IMFs.

- Answer a

-

The viscosity increases as the molecular weight (size) of the molecules increases. Additionally, the more polar the molecule, the more viscous.

- Answer b

-

The surface tension increases as the molecular weight of the molecule increases. Additionally, the more polar the molecule, the higher the surface tension.

PROBLEM \(\PageIndex{4}\)

You may have heard someone use the figure of speech “slower than molasses in winter” to describe a process that occurs slowly. Explain why this is an apt idiom, using concepts of molecular size and shape, molecular interactions, and the effect of changing temperature.

- Answer

-

Temperature has an effect on intermolecular forces: the higher the temperature, the greater the kinetic energies of the molecules and the greater the extent to which their intermolecular forces are overcome, and so the more fluid (less viscous) the liquid; the lower the temperature, the lesser the intermolecular forces are overcome, and so the more viscous the liquid.

PROBLEM \(\PageIndex{5}\)

It is often recommended that you let your car engine run idle to warm up before driving, especially on cold winter days. While the benefit of prolonged idling is dubious, it is certainly true that a warm engine is more fuel efficient than a cold one. Explain the reason for this.

- Answer

-

The fluids in the engine are warmer, decreasing their viscosity, which aids in lubricating the moving parts of the engine causing it to run smoother.

PROBLEM \(\PageIndex{6}\)

The surface tension and viscosity of water at several different temperatures are given in this table.

| Water | Surface Tension (mN/m) | Viscosity (mPa s) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 °C | 75.6 | 1.79 |

| 20 °C | 72.8 | 1.00 |

| 60 °C | 66.2 | 0.47 |

| 100 °C | 58.9 | 0.28 |

- As temperature increases, what happens to the surface tension of water? Explain why this occurs, in terms of molecular interactions and the effect of changing temperature.

- As temperature increases, what happens to the viscosity of water? Explain why this occurs, in terms of molecular interactions and the effect of changing temperature.

- Answer a

-

As the water reaches higher temperatures, the increased kinetic energies of its molecules are more effective in overcoming hydrogen bonding, and so its surface tension decreases. Surface tension and intermolecular forces are directly related.

- Answer b

-

The same trend in viscosity is seen as in surface tension, and for the same reason.

Have a video solution request?

Let your professors know here.

***Please know that you are helping future students - videos will be made in time for next term's class.

Contributors and Attributions

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

- Adelaide Clark, Oregon Institute of Technology

Feedback

Think one of the answers above is wrong? Let us know here.