7.2: Brønsted-Lowry Acids and Bases

- Page ID

- 221509

Learning Objectives

- Identify a Brønsted-Lowry acid and a Brønsted-Lowry base.

- Identify conjugate acid-base pairs in an acid-base reaction.

The Arrhenius definition of acid and base is limited to substances that can generate H+ and the OH− ions in aqueous solutions. Although this is useful because water is a common solvent, it does not explain the acidity and basicity of all substances. For example, when ammonia (NH3) is dissolved in water, a basic solution is formed. But how can this be possible if NH3 has no OH- in its chemical formula?

In 1923, Danish chemist Johannes Brønsted and English chemist Thomas Lowry independently proposed new definitions for acids and bases, ones that focus on proton transfer. A Brønsted-Lowry acid is any species that can donate a proton (H+) to another molecule. A Brønsted-Lowry base is any species that can accept a proton from another molecule. In short, a Brønsted-Lowry acid is a proton donor (PD), while a Brønsted-Lowry base is a proton acceptor (PA).

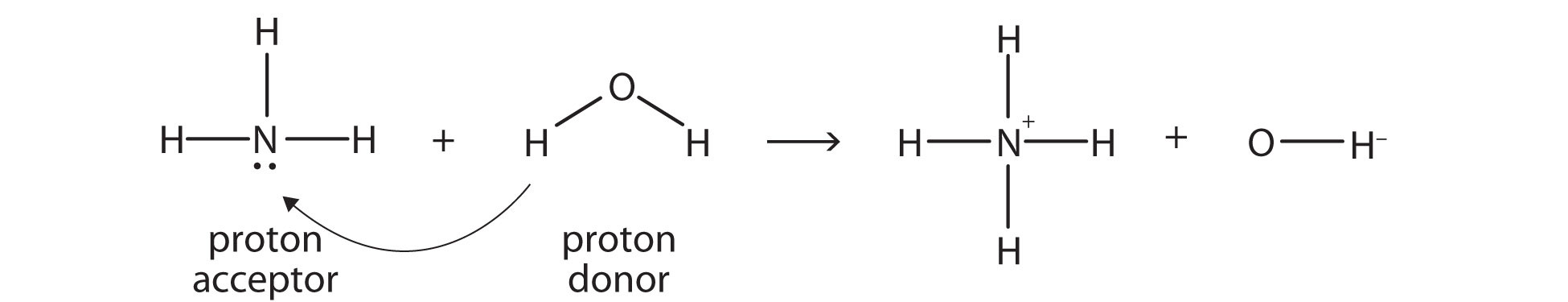

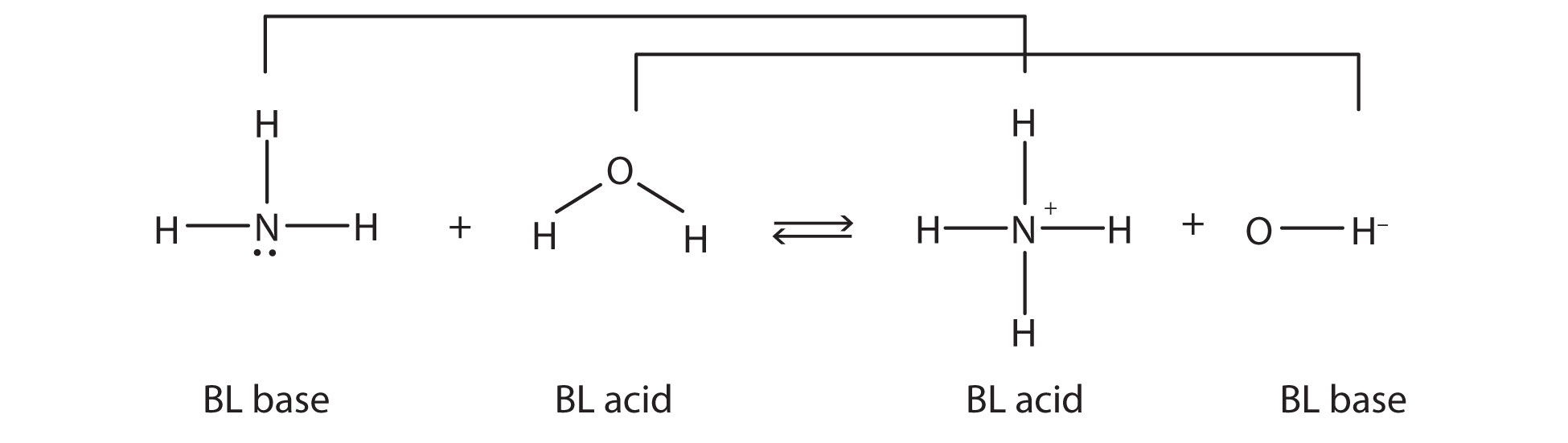

According to this theory, ammonia (NH3) is a base even though it does not contain OH− ions in its formula. Instead, it generates OH− ions as the product of a proton-transfer reaction with H2O molecules; NH3 acts like a Brønsted-Lowry base, and H2O acts like a Brønsted-Lowry acid:

A reaction with water is called hydrolysis; we say that NH3 hydrolyzes to make NH4+ ions and OH− ions. Therefore, this theory explains the acidity and basicity of compounds that do not contain H+ or HO- in their formulas.

Relationship between Arrhenius and Brønsted-Lowry theories

It is easy to see that the Brønsted-Lowry definition covers the Arrhenius definition of acids and bases. Consider the process of dissolving HCl(g) in water to make an aqueous solution of hydrochloric acid. The process can be written as follows:

\[\ce{HCl(g) + H2O(ℓ) → H3O+(aq) + Cl^{-}(aq)} \nonumber\nonumber \]

HCl(g) is the proton donor and therefore a Brønsted-Lowry acid, while H2O is the proton acceptor and a Brønsted-Lowry base. The H+ ion is just a bare proton, and it is rather clear that bare protons are not floating around in an aqueous solution. Instead, chemistry has defined the hydronium ion(H3O+) as the actual chemical species that represents an H+ ion. H+ ions and H3O+ ions are often considered interchangeable when writing chemical equations (although a properly balanced chemical equation should also include the additional H2O).

These two examples (NH3 in water and HCl in water) show that H2O can act as both a proton donor and a proton acceptor, depending on what other substance is in the chemical reaction. A substance that can act as a proton donor or a proton acceptor is called amphiprotic. Water is probably the most common amphiprotic substance we will encounter, but other substances are also amphiprotic.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Identify the Brønsted-Lowry acid and the Brønsted-Lowry base in this chemical equation.

\[\ce{C6H5OH + NH2^{-} -> C6H5O^{-} + NH3} \nonumber\nonumber \]

Solution

The C6H5OH molecule is losing an H+; it is the proton donor and the Brønsted-Lowry acid. The NH2− ion (called the amide ion) is accepting the H+ ion to become NH3, so it is the Brønsted-Lowry base.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\): Aluminum Ions in Solution

Identify the Brønsted-Lowry acid and the Brønsted-Lowry base in this chemical equation.

\[\ce{Al(H2O)6^{3+} + H2O -> Al(H2O)5(OH)^{2+} + H3O^{+}} \nonumber\nonumber \]

- Answer

-

Brønsted-Lowry acid: Al(H2O)63+; Brønsted-Lowry base: H2O

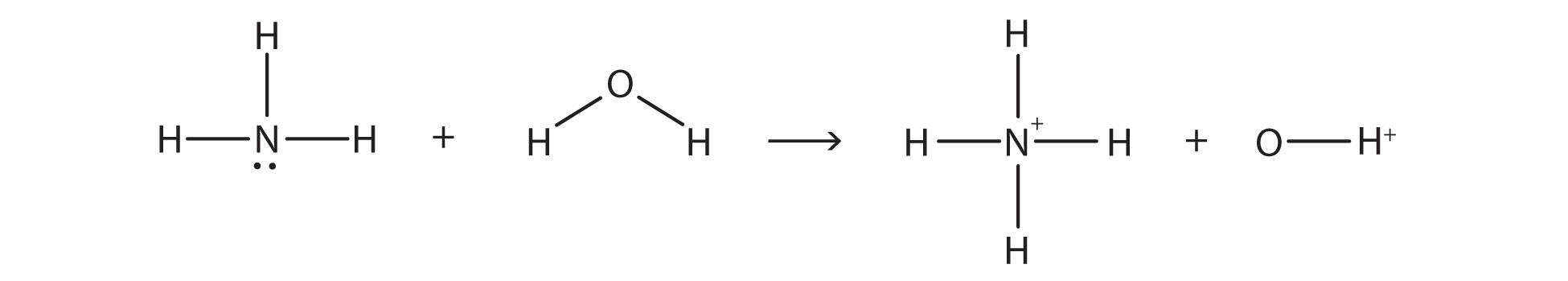

In the reaction between NH3 and H2O,

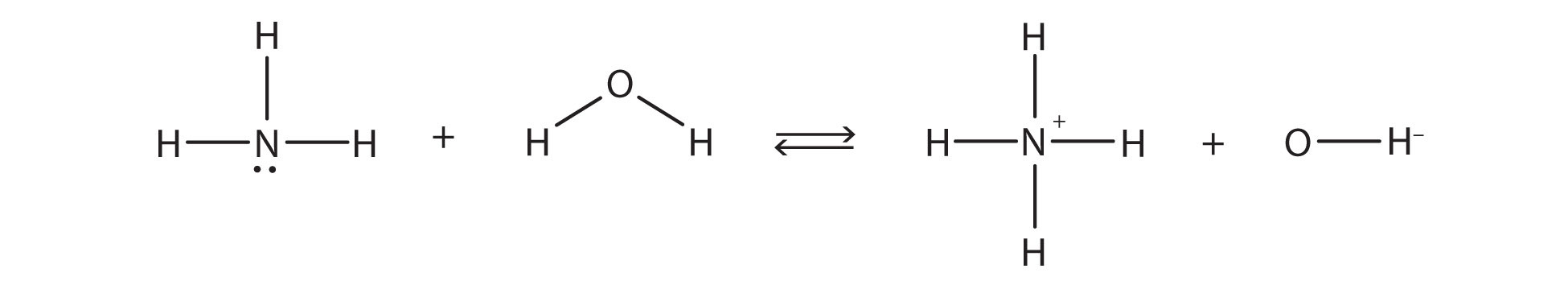

the chemical reaction does not go to completion; rather, the reverse process occurs as well, and eventually the two processes cancel out any additional change. At this point, we say the chemical reaction is at equilibrium. Both processes still occur, but any net change by one process is countered by the same net change of the other process; it is a dynamic, rather than a static, equilibrium. Because both reactions are occurring, it makes sense to use a double arrow instead of a single arrow:

What do you notice about the reverse reaction? The NH4+ ion is donating a proton to the OH− ion, which is accepting it. This means that the NH4+ ion is acting as the proton donor, or Brønsted-Lowry acid, while the OH− ion, the proton acceptor, is acting as a Brønsted-Lowry base. The reverse reaction is also a Brønsted-Lowry acid base reaction:

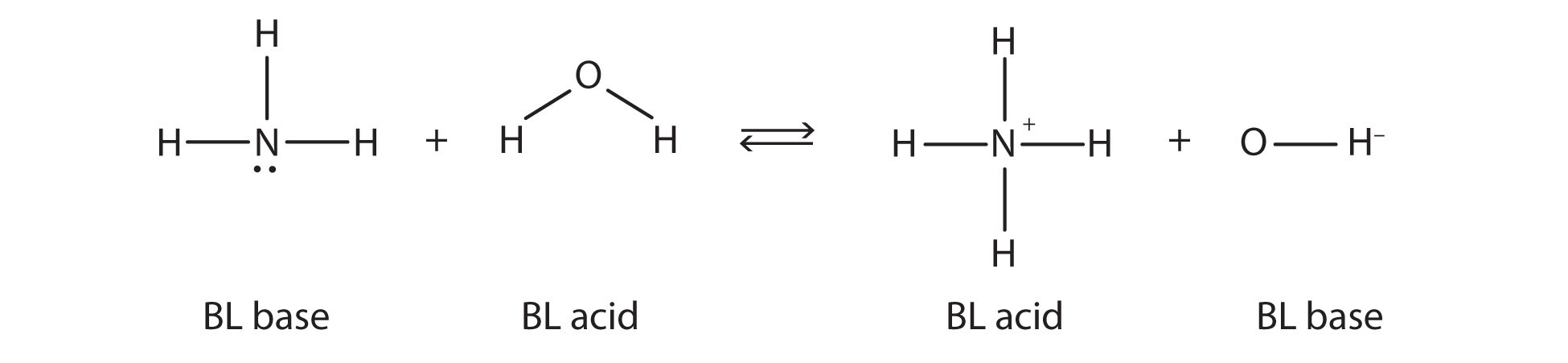

This means that both reactions are acid-base reactions by the Brønsted-Lowry definition. If you consider the species in this chemical reaction, two sets of similar species exist on both sides. Within each set, the two species differ by a proton in their formulas, and one member of the set is a Brønsted-Lowry acid, while the other member is a Brønsted-Lowry base. These sets are marked here:

The two sets—NH3/NH4+ and H2O/OH−—are called conjugate acid-base pairs. We say that NH4+ is the conjugate acid of NH3, OH− is the conjugate base of H2O, and so forth. Every Brønsted-Lowry acid-base reaction can be labeled with two conjugate acid-base pairs. One easy way to identify a conjugate acid-base pair is by looking at the chemical formulas: a conjugate acid-base pair has a H+ difference in their formulas, i.e., NH3/NH4+ or HCl/Cl-. The acid member of the pairs always carries the H+.

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Identify the conjugate acid-base pairs in this equilibrium.

\[(CH_{3})_{3}N+H_{2}O\rightleftharpoons (CH_{3})_{3}NH^{+}+OH^{-} \nonumber\nonumber \]

Solution

One pair is H2O and OH−, where H2O has one more H+ and is the conjugate acid, while OH− has one less H+ and is the conjugate base. The other pair consists of (CH3)3N and (CH3)3NH+, where (CH3)3NH+ is the conjugate acid (it has an additional proton) and (CH3)3N is the conjugate base.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

Identify the conjugate acid-base pairs in this equilibrium.

\[NH_{2}^{-}+H_{2}O\rightleftharpoons NH_{3}+OH^{-} \nonumber\nonumber \]

- Answer

-

H2O (acid) and OH− (base); NH2− (base) and NH3 (acid)

Chemistry is Everywhere: Household Acids and Bases

Many household products are acids or bases. For example, the owner of a swimming pool may use muriatic acid to clean the pool. Muriatic acid is another name for HCl(aq). In Section 4.6, vinegar was mentioned as a dilute solution of acetic acid [HC2H3O2(aq)]. In a medicine chest, one may find a bottle of vitamin C tablets; the chemical name of vitamin C is ascorbic acid (HC6H7O6).

One of the more familiar household bases is NH3, which is found in numerous cleaning products. NH3 is a base because it increases the OH− ion concentration by reacting with H2O:

NH3(aq) + H2O(ℓ) → NH4+(aq) + OH−(aq)Many soaps are also slightly basic because they contain compounds that act as Brønsted-Lowry bases, accepting protons from H2O and forming excess OH− ions. This is one explanation for why soap solutions are slippery.

Perhaps the most dangerous household chemical is the lye-based drain cleaner. Lye is a common name for NaOH, although it is also used as a synonym for KOH. Lye is an extremely caustic chemical that can react with grease, hair, food particles, and other substances that may build up and clog a water pipe. Unfortunately, lye can also attack body tissues and other substances in our bodies. Thus when we use lye-based drain cleaners, we must be very careful not to touch any of the solid drain cleaner or spill the water it was poured into. Safer, non-lye drain cleaners (like the one in the accompanying figure) use peroxide compounds to react on the materials in the clog and clear the drain.

Key Takeaways

- A Brønsted-Lowry acid is a proton donor; a Brønsted-Lowry base is a proton acceptor.

- Acid-base reactions include two sets of conjugate acid-base pairs.