6.5: Solving Acid-Base Problems

- Page ID

- 164767

Skills to Develop

- Carry out equilibrium calculations for weak acid–base systems

The Ionization of Weak Acids and Weak Bases

Many acids and bases are weak; that is, they do not ionize fully in aqueous solution. A solution of a weak acid in water is a mixture of the nonionized acid, hydronium ion, and the conjugate base of the acid, with the nonionized acid present in the greatest concentration. Thus, a weak acid increases the hydronium ion concentration in an aqueous solution (but not as much as the same amount of a strong acid).

Acetic acid (\(\ce{CH3CO2H}\)) is a weak acid. When we add acetic acid to water, it ionizes to a small extent according to the equation:

\[\ce{CH3CO2H}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{CH3CO2-}(aq)\]

giving an equilibrium mixture with most of the acid present in the nonionized (molecular) form. This equilibrium, like other equilibria, is dynamic; acetic acid molecules donate hydrogen ions to water molecules and form hydronium ions and acetate ions at the same rate that hydronium ions donate hydrogen ions to acetate ions to reform acetic acid molecules and water molecules. We can tell by measuring the pH of an aqueous solution of known concentration that only a fraction of the weak acid is ionized at any moment (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). The remaining weak acid is present in the nonionized form.

For acetic acid, at equilibrium:

\[K_\ce{a}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][CH3CO2- ]}{[CH3CO2H]}}=1.8 \times 10^{−5}\]

| Ionization Reaction | Ka at 25 °C |

|---|---|

| \(\ce{HSO4- + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + SO4^2-}\) | 1.2 × 10−2 |

| \(\ce{HF + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + F-}\) | 3.5 × 10−4 |

| \(\ce{HNO2 + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + NO2-}\) | 4.6 × 10−4 |

| \(\ce{HNCO + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + NCO-}\) | 2 × 10−4 |

| \(\ce{HCO2H + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + HCO2-}\) | 1.8 × 10−4 |

| \(\ce{CH3CO2H + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + CH3CO2-}\) | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| \(\ce{HCIO + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + CIO-}\) | 2.9 × 10−8 |

| \(\ce{HBrO + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + BrO-}\) | 2.8 × 10−9 |

| \(\ce{HCN + H2O ⇌ H3O+ + CN-}\) | 4.9 × 10−10 |

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) gives the ionization constants for several weak acids. Acid ionization constants can be determined by measuring the equilibrium concentrations of a weak acid and its conjugate base in solution.

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Determination of Ka from Equilibrium Concentrations

Acetic acid is the principal ingredient in vinegar; that's why it tastes sour. At equilibrium, a solution contains [CH3CO2H] = 0.0787 M and \(\ce{[H3O+]}=\ce{[CH3CO2- ]}=0.00118\:M\) . What is the value of Ka for acetic acid?

Solution

We are asked to calculate an equilibrium constant from equilibrium concentrations. At equilibrium, the value of the equilibrium constant is equal to the reaction quotient for the reaction:

\[\ce{CH3CO2H}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{CH3CO2-}(aq) \]

\[K_\ce{a}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][CH3CO2- ]}{[CH3CO2H]}}=\dfrac{(0.00118)(0.00118)}{0.0787}=1.77×10^{−5} \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

What is the equilibrium constant for the ionization of the \(\ce{HSO4-}\) ion, the weak acid used in some household cleansers:

\[\ce{HSO4-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq) \]

In one mixture of NaHSO4 and Na2SO4 at equilibrium, \(\ce{[H3O+]}\) = 0.027 M; \(\ce{[HSO4- ]}=0.29\:M\); and \(\ce{[SO4^2- ]}=0.13\:M\).

- Answer

-

\(K_a\) for \(\ce{HSO_4^-}= 1.2 ×\times 10^{−2}\)

The situation for basic solutions is similar. At equilibrium, a solution of a weak base in water is a mixture of the nonionized base, the conjugate acid of the weak base, and hydroxide ion with the nonionized base present in the greatest concentration.

For example, a solution of the weak base trimethylamine, (CH3)3N, in water reacts according to the equation:

\[\ce{(CH3)3N}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{(CH3)3NH+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq)\]

This gives an equilibrium mixture with most of the base present as the nonionized amine. This equilibrium is analogous to that described for weak acids.

We can confirm by measuring the pH of an aqueous solution of a weak base of known concentration that only a fraction of the base reacts with water (Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\)). The remaining weak base is present as the unreacted form. The equilibrium constant for the ionization of a weak base, Kb, is called the ionization constant of the weak base, and is equal to the reaction quotient when the reaction is at equilibrium. For trimethylamine, at equilibrium:

\[K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[(CH3)3NH+][OH- ]}{[(CH3)3N]}}\]

The ionization constants of several weak bases are given in Table \(\PageIndex{2}\). These values can be used in equilibrium calculations analogously to acid ionization constants.

| Ionization Reaction | Kb at 25 °C |

|---|---|

| \(\ce{(CH3)2NH + H2O ⇌ (CH3)2NH2+ + OH-}\) | 5.9 × 10−4 |

| \(\ce{CH3NH2 + H2O ⇌ CH3NH3+ + OH-}\) | 4.4 × 10−4 |

| \(\ce{(CH3)3N + H2O ⇌ (CH3)3NH+ + OH-}\) | 6.3 × 10−5 |

| \(\ce{NH3 + H2O ⇌ NH4+ + OH-}\) | 1.8 × 10−5 |

| \(\ce{C6H5NH2 + H2O ⇌ C6N5NH3+ + OH-}\) | 4.3 × 10−10 |

Example \(\PageIndex{2}\): Determination of Kb from Equilibrium Concentrations

Caffeine, C8H10N4O2 is a weak base. What is the value of Kb for caffeine if a solution at equilibrium has [C8H10N4O2] = 0.050 M, \(\ce{[C8H10N4O2H+]}\) = 5.0 × 10−3 M, and [OH−] = 2.5 × 10−3 M?

Solution

At equilibrium, the value of the equilibrium constant is equal to the reaction quotient for the reaction:

\[\ce{C8H10N4O2}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{C8H10N4O2H+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) \]

\[K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[C8H10N4O2H+][OH- ]}{[C8H10N4O2]}}=\dfrac{(5.0×10^{−3})(2.5×10^{−3})}{0.050}=2.5×10^{−4} \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{2}\)

What is the equilibrium constant for the ionization of the \(\ce{HPO4^2-}\) ion, a weak base:

\[\ce{HPO4^2-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H2PO4-}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) \]

In a solution containing a mixture of NaH2PO4 and Na2HPO4 at equilibrium, [OH−] = 1.3 × 10−6 M; \(\ce{[H2PO4- ]}=0.042\:M\) ; and \(\ce{[HPO4^2- ]}=0.341\:M\).

- Answer

-

Kb for \(\ce{HPO4^2-}=1.6×10^{−7} \)

Equilibrium Calculations with pH

In practice, chemists almost never measure the equilibrium concentrations of both the weak acid and conjugate base forms, but rather determine them from the known total acid concentration and the measured pH. Remember that pH gives the concentration of \(\ce{H3O+}\) in a solution - this quantity can then be used in the acid dissociation equilibrium. For weak bases, pH can be converted to pOH to relate to the concentration of \(\ce{OH-}\) in the base dissociation equilibrium. Conversely, if the Ka or Kb is known, the pH can be predicted from the total acid/base concentration using the same calculational approach.

Example \(\PageIndex{3}\): Determination of Ka or Kb from pH

The pH of a 0.0516-M solution of nitrous acid, \(\ce{HNO2}\), is 2.34. What is its Ka?

Solution

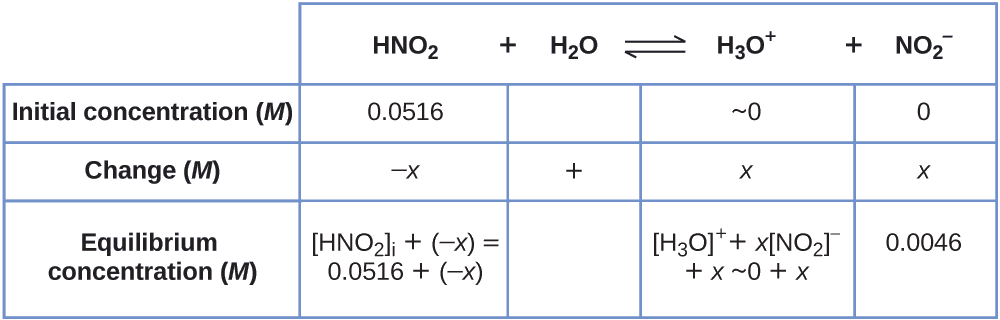

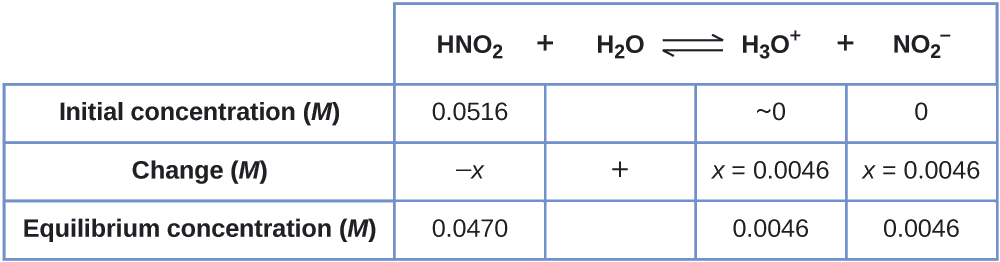

We determine an equilibrium constant starting with the initial concentrations of HNO2, \(\ce{H3O+}\), and \(\ce{NO2-}\) as well as one of the final concentrations, the concentration of hydronium ion at equilibrium. (Remember that pH is simply another way to express the concentration of hydronium ion.)

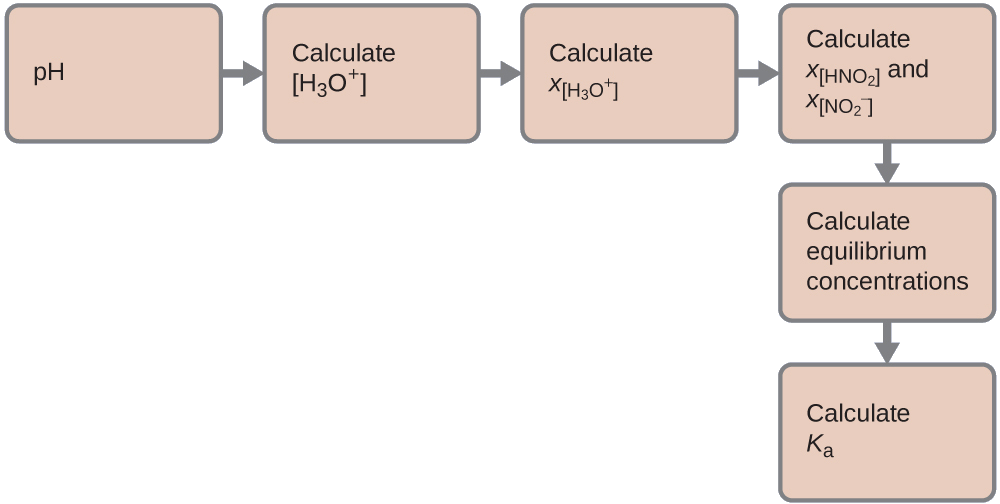

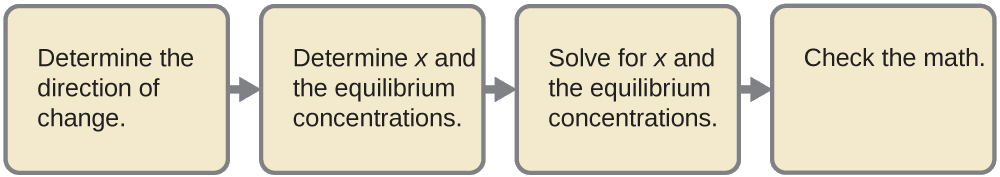

We can solve this problem with the following steps in which x is a change in concentration of a species in the reaction:

We can summarize the various concentrations and changes as shown here (the concentration of water does not appear in the expression for the equilibrium constant, so we do not need to consider its concentration):

To get the various values in the ICE (Initial, Change, Equilibrium) table, we first calculate \(\ce{[H3O+]}\), the equilibrium concentration of \(\ce{H3O+}\), from the pH:

\[\ce{[H3O+]}=10^{−2.34}=0.0046\:M \]

The change in concentration of \(\ce{H3O+}\), \(x_{\ce{[H3O+]}}\) , is the difference between the equilibrium concentration of H3O+, which we determined from the pH, and the initial concentration, \(\mathrm{[H_3O^+]_i}\) . The initial concentration of \(\ce{H3O+}\) is its concentration in pure water, which is so much less than the final concentration that we approximate it as zero (~0).

The change in concentration of \(\ce{NO2-}\) is equal to the change in concentration of \(\ce{[H3O+]}\) . For each 1 mol of \(\ce{H3O+}\) that forms, 1 mol of \(\ce{NO2-}\) forms. The equilibrium concentration of HNO2 is equal to its initial concentration plus the change in its concentration.

Now we can fill in the ICE table with the concentrations at equilibrium, as shown here:

Finally, we calculate the value of the equilibrium constant using the data in the table:

\[K_\ce{a}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][NO2- ]}{[HNO2]}}=\dfrac{(0.0046)(0.0046)}{(0.0470)}=4.5×10^{−4} \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{3}\)

The pH of a solution of household ammonia, a 0.950-M solution of NH3, is 11.612. What is Kb for NH3?

- Answer

-

\(K_b = 1.8 × 10^{−5}\)

Example \(\PageIndex{4}\): Equilibrium Concentrations in a Solution of a Weak Acid

Formic acid, HCO2H, is the irritant that causes the body’s reaction to ant stings.

What is the concentration of hydronium ion and the pH in a 0.534-M solution of formic acid?

Solution

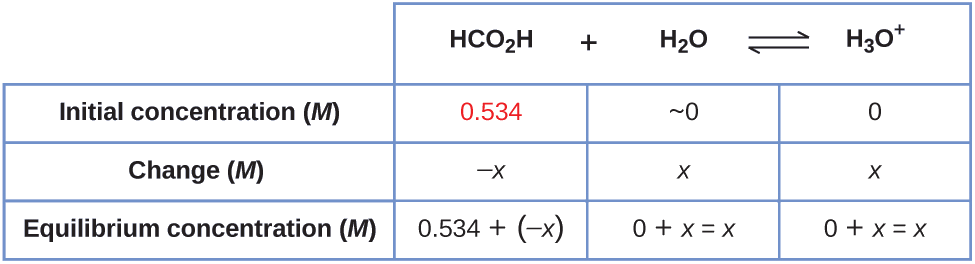

1. Determine x and equilibrium concentrations. The equilibrium expression is:

\[\ce{HCO2H}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{HCO2-}(aq) \]

The concentration of water does not appear in the expression for the equilibrium constant, so we do not need to consider its change in concentration when setting up the ICE table.

The table shows initial concentrations (concentrations before the acid ionizes), changes in concentration, and equilibrium concentrations follows (the data given in the problem appear in color):

2. Solve for x and the equilibrium concentrations. At equilibrium:

\[\begin{align*} K_\ce{a} &=1.8×10^{−4}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][HCO2- ]}{[HCO2H]}} \\[4pt] &=\dfrac{(x)(x)}{0.534−x}=1.8×10^{−4} \end{align*}\]

Now solve for x. Because the initial concentration of acid is reasonably large and Ka is very small, we assume that x << 0.534, which permits us to simplify the denominator term as (0.534 − x) = 0.534. This gives:

\[K_\ce{a}=1.8×10^{−4}=\dfrac{x^{2}}{0.534} \]

Solve for x as follows:

To check the assumption that \(x\) is small compared to 0.534, we calculate:

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{x}{0.534} &=\dfrac{9.8×10^{−3}}{0.534} \\[4pt] &=1.8×10^{−2} \, \textrm{(1.8% of 0.534)} \end{align*}\]

x is less than 5% of the initial concentration; the assumption is valid.

We find the equilibrium concentration of hydronium ion in this formic acid solution from its initial concentration and the change in that concentration as indicated in the last line of the table:

The pH of the solution can be found by taking the negative log of the \(\ce{[H3O+]}\), so:

\(pH = −\log(9.8×10^{−3})=2.01\)

Exercise \(\PageIndex{4}\): acetic acid

Only a small fraction of a weak acid ionizes in aqueous solution. What is the percent ionization of acetic acid in a 0.100-M solution of acetic acid, CH3CO2H?

\[\ce{CH3CO2H}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{CH3CO2-}(aq) \hspace{20px} K_\ce{a}=1.8×10^{−5} \]

- Hint

-

Determine \(\ce{[CH3CO2- ]}\) at equilibrium.) Recall that the percent ionization is the fraction of acetic acid that is ionized × 100, or \(\ce{\dfrac{[CH3CO2- ]}{[CH3CO2H]_{initial}}}×100\).

- Answer

-

percent ionization = 1.3%

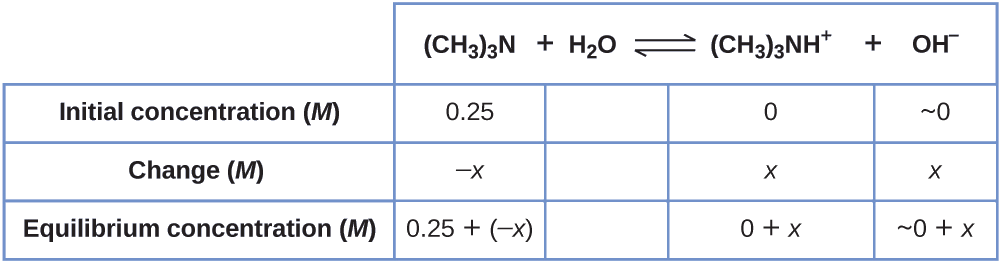

The following example shows that the concentration of products produced by the ionization of a weak base can be determined by the same series of steps used with a weak acid.

Example \(\PageIndex{5}\): Equilibrium Concentrations in a Solution of a Weak Base

Find the concentration of hydroxide ion in a 0.25-M solution of trimethylamine, a weak base:

\[\ce{(CH3)3N}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{(CH3)3NH+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) \hspace{20px} K_\ce{b}=6.3×10^{−5} \]

Solution This problem requires that we calculate an equilibrium concentration by determining concentration changes as the ionization of a base goes to equilibrium. The solution is approached in the same way as that for the ionization of formic acid in Example \(\PageIndex{6}\). The reactants and products will be different and the numbers will be different, but the logic will be the same:

1. Determine x and equilibrium concentrations. The table shows the changes and concentrations:

2. Solve for x and the equilibrium concentrations. At equilibrium:

\[K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[(CH3)3NH+][OH- ]}{[(CH3)3N]}}=\dfrac{(x)(x)}{0.25−x=}6.3×10^{−5} \]

If we assume that x is small relative to 0.25, then we can replace (0.25 − x) in the preceding equation with 0.25. Solving the simplified equation gives:

This change is less than 5% of the initial concentration (0.25), so the assumption is justified.

Recall that, for this computation, x is equal to the equilibrium concentration of hydroxide ion in the solution (see earlier tabulation):

\[(\ce{[OH- ]}=~0+x=x=4.0×10^{−3}\:M \]

Then calculate pOH as follows:

Using the relation introduced in the previous section of this chapter:

permits the computation of pH:

Check the work. A check of our arithmetic shows that Kb = 6.3 × 10−5.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{5}\)

- Show that the calculation in Step 2 of this example gives an x of 4.3 × 10−3 and the calculation in Step 3 shows Kb = 6.3 × 10−5.

- Find the concentration of hydroxide ion in a 0.0325-M solution of ammonia, a weak base with a Kb of 1.76 × 10−5. Calculate the percent ionization of ammonia, the fraction ionized × 100, or \(\ce{\dfrac{[NH4+]}{[NH3]}}×100 \%\)

- Answer a

-

\(7.56 × 10^{−4}\, M\), 2.33%

- Answer b

-

2.33%

Some weak acids and weak bases ionize to such an extent that the simplifying assumption that x is small relative to the initial concentration of the acid or base is inappropriate. As we solve for the equilibrium concentrations in such cases, we will see that we cannot neglect the change in the initial concentration of the acid or base, and we must solve the equilibrium equations by using the quadratic equation.

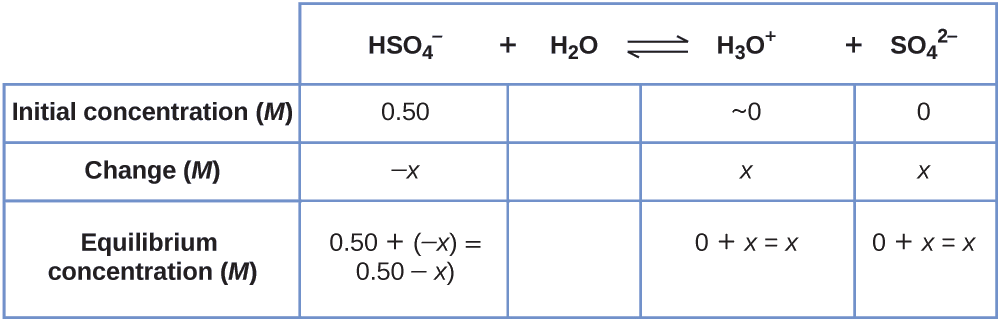

Example \(\PageIndex{6}\): Equilibrium Concentrations in a Solution of a Weak Acid

Sodium bisulfate, NaHSO4, is used in some household cleansers because it contains the \(\ce{HSO4-}\) ion, a weak acid. What is the pH of a 0.50-M solution of \(\ce{HSO4-}\)?

\[\ce{HSO4-}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{H3O+}(aq)+\ce{SO4^2-}(aq) \hspace{20px} K_\ce{a}=1.2×10^{−2} \]

Solution

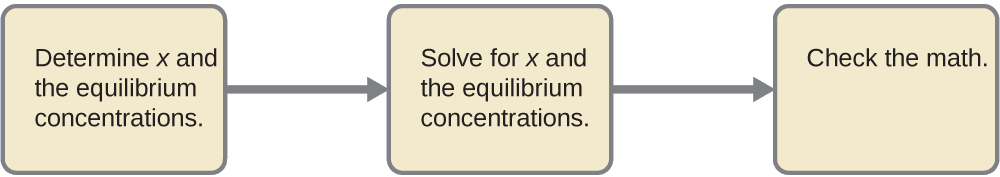

We need to determine the equilibrium concentration of the hydronium ion that results from the ionization of \(\ce{HSO4-}\) so that we can use \(\ce{[H3O+]}\) to determine the pH. As in the previous examples, we can approach the solution by the following steps:

1. Determine x and equilibrium concentrations. This table shows the changes and concentrations:

2. Solve for x and the concentrations.

As we begin solving for x, we will find this is more complicated than in previous examples. As we discuss these complications we should not lose track of the fact that it is still the purpose of this step to determine the value of x.

At equilibrium:

\[K_\ce{a}=1.2×10^{−2}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][SO4^2- ]}{[HSO4- ]}}=\dfrac{(x)(x)}{0.50−x} \]

If we assume that x is small and approximate (0.50 − x) as 0.50, we find:

When we check the assumption, we confirm:

\[\dfrac{x}{\mathrm{[HSO_4^- ]_i}} \overset{?}{\le} 0.05 \]

which for this system is

\[\dfrac{x}{0.50}=\dfrac{7.7×10^{−2}}{0.50}=0.15(15\%) \]

The value of \(x\) is not less than 5% of 0.50, so the assumption is not valid. We need the quadratic formula to find \(x\).

The equation:

\[K_\ce{a}=1.2×10^{−2}=\dfrac{(x)(x)}{0.50−x} \]

gives

\[6.0×10^{−3}−1.2×10^{−2}x=x^{2+} \]

or

\[x^{2+}+1.2×10^{−2}x−6.0×10^{−3}=0\ \]

This equation can be solved using the quadratic formula. For an equation of the form

x is given by the equation:

\[x=\dfrac{−b±\sqrt{b^{2+}−4ac}}{2a} \]

In this problem, a = 1, b = 1.2 × 10−3, and c = −6.0 × 10−3.

Solving for x gives a negative root (which cannot be correct since concentration cannot be negative) and a positive root:

\[x=7.2×10^{−2} \]

Now determine the hydronium ion concentration and the pH:

\[\begin{align*} \ce{[H3O+]} &=~0+x=0+7.2×10^{−2}\:M \\[4pt] &=7.2×10^{−2}\:M \end{align*}\]

The pH of this solution is:

\[\mathrm{pH=−log[H_3O^+]=−log7.2×10^{−2}=1.14} \]

Exercise \(\PageIndex{6}\)

- Show that the quadratic formula gives \(x = 7.2 × 10^{−2}\).

- Calculate the pH in a 0.010-M solution of caffeine, a weak base:

\[\ce{C8H10N4O2}(aq)+\ce{H2O}(l)⇌\ce{C8H10N4O2H+}(aq)+\ce{OH-}(aq) \hspace{20px} K_\ce{b}=2.5×10^{−4} \]

- Hint

-

It will be necessary to convert [OH−] to \(\ce{[H3O+]}\) or pOH to pH toward the end of the calculation.

- Answer

-

pH 11.16

Summary

The acid or base ionization constant

Key Equations

- \(K_\ce{a}=\ce{\dfrac{[H3O+][A- ]}{[HA]}}\)

- \(K_\ce{b}=\ce{\dfrac{[HB+][OH- ]}{[B]}}\)

Glossary

- acid ionization constant (Ka)

- equilibrium constant for the ionization of a weak acid

- base ionization constant (Kb)

- equilibrium constant for the ionization of a weak base

Contributors

Paul Flowers (University of North Carolina - Pembroke), Klaus Theopold (University of Delaware) and Richard Langley (Stephen F. Austin State University) with contributing authors. Textbook content produced by OpenStax College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 license. Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/85abf193-2bd...a7ac8df6@9.110).

- Anna Christianson, Bellarmine University