12.4: General Properties of Time Correlation Functions

- Page ID

- 5288

Define a time correlation function between two quantities \(A (x) \) and \(B (x) \) by

\[\begin{align*} C_{AB} (t) &= \langle A(0)B(t)\rangle \\[4pt] &= \int d{\rm x}f({\rm x})A({\rm x})e^{iLt}B({\rm x}) \end{align*} \]

The following properties follow immediately from the above definition:

Property 1

\[\langle A(0)B(t)\rangle = \langle A(-t)B(0)\rangle \nonumber \]

Property 2

\[C_{AB}(0) = \langle A({\rm x})B({\rm x})\rangle \nonumber \] Thus, if \(A = B \), then

\[C_{AA}(t) = \langle A(0)A(t)\rangle \nonumber \]

known as the autocorrelation function of \(A\), and

\[C_{AA}(0) = \langle A^2\rangle \nonumber \]

If we define \(\delta A = A - \langle A \rangle \), then

\[C_{\delta A\delta A}(0) = \langle (\delta A)^2\rangle =\langle ( A - \langle A \rangle )^2 \rangle = \langle A^2\rangle - \langle A\rangle^2 \nonumber \]

which just measures the fluctuations in the quantity \(A\).

Property 3

A time correlation function may be evaluated as a time average, assuming the system is ergodic. In this case, the phase space average may be equated to a time average, and we have

\[C_{AB}(t) = \lim_{T\rightarrow\infty}{1 \over T-t}\int_0^{T-t}ds A({\rm x}(s))B({\rm x}(t+s)) \nonumber \]

which is valid for \( t<<T \). In molecular dynamics simulations, where the phase space trajectory is determined at discrete time steps, the integral is expressed as a sum

\[ C_{AB}(k\Delta t) = {1 \over N-k}\sum_{j=1}^{N-k}A({\rm x}_k)B({\rm x}_{k+j})\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;k=0,1,2,...,N_c \nonumber \]

where \(N\) is the total number of time steps, \(\Delta t \) is the time step and \(N_c << N \).

Property 4: Onsager regression hypothesis

In the long time limit, \(A \) and \(B\) eventually become uncorrelated from each other so that the time correlation function becomes

\[ C_{AB}(t) = \langle A(0)B(t)\rangle \rightarrow \langle A\rangle\langle B\rangle \nonumber \]

For the autocorrelation function of \(A\), this becomes

\[ C_{AA}(t)\rightarrow \langle A\rangle^2 \nonumber \]

Thus, \(C_{AA} (t) \) decays from \(\langle A^2 \rangle \) at \( t = 0\) to \( \langle A^2 \rangle \) as \(t \rightarrow \infty \).

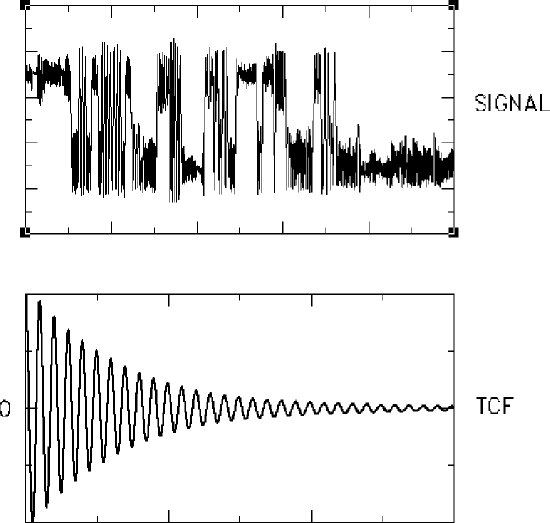

An example of a signal and its time correlation function appears in Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\). In this case, the signal is the magnitude of the velocity along the bond of a diatomic molecule interacting with a Lennard-Jones bath. Its time correlation function is shown beneath the signal:

Over time, it can be seen that the property being autocorrelated eventually becomes uncorrelated with itself.