5.2: The Two Major Classes of Isomers

- Page ID

- 30356

Isomers are different compounds that have the same molecular formula. When the group of atoms that make up the molecules of different isomers are bonded together in fundamentally different ways, we refer to such compounds as constitutional isomers. For example, in the case of the C4H8hydrocarbons, most of the isomers are constitutional. Shorthand structures for four of these isomers are shown below with their IUPAC names.

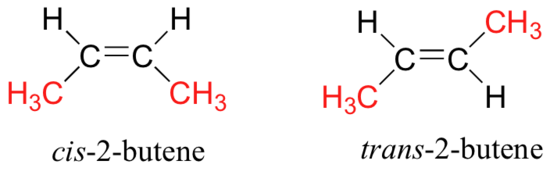

Note that the twelve atoms that make up these isomers are bonded in very different ways. As is true for all constitutional isomers, each different compound has a different IUPAC name. Furthermore, the molecular formula provides information about some of the structural features that must be present in the isomers. Since the formula C4H8 has two fewer hydrogens than the four-carbon alkane butane (C4H10), all the isomers having this composition must incorporate either a ring or a double bond. A fifth possible isomer of formula C4H8 is CH3CH=CHCH3. This would be named 2-butene according to the IUPAC rules; however, a close inspection of this molecule indicates it has two possible structures. These isomers may be isolated as distinct compounds, having characteristic and different properties. They are shown here with the designations cis and trans.

The bonding patterns of the atoms in these two isomers are essentially equivalent, the only difference being the relative configuration of the two methyl groups and the two associated hydrogen atoms about the double bond. In the cis isomer the methyl groups are on the same side; whereas they are on opposite sides in the trans isomer. Isomers that differ only in the spatial orientation of their component atoms are called stereoisomers. Stereoisomers always require that an additional nomenclature prefix be added to the IUPAC name in order to indicate their spatial orientation.

Stereoisomers are also observed in certain disubstituted (and higher substituted) cyclic compounds. Unlike the relatively flat molecules of alkenes, substituted cycloalkanes must be viewed as three-dimensional configurations in order to appreciate the spatial orientations of the substituents. By agreement, chemists use heavy, wedge-shaped bonds to indicate a substituent located above the average plane of the ring, and a hatched line for bonds to atoms or groups located below the ring. As in the case of the 2-butene stereoisomers, disubstituted cycloalkane stereoisomers may be designated by nomenclature prefixes such as cis and trans. The stereoisomeric 1,2-dibromocyclopentanes below are an example.

In general, if any two sp3 carbons in a ring have two different substituent groups (not counting other ring atoms) stereoisomerism is possible. This is similar to the substitution pattern that gives rise to stereoisomers in alkenes; indeed, one might view a double bond as a two-membered ring. Four other examples of this kind of stereoisomerism in cyclic compounds are shown below.

If more than two ring carbons have different substituents (not counting other ring atoms) the stereochemical notation distinguishing the various isomers becomes more complex. However, we can always state the relationship of any two substituents using cis or trans. For example, in the trisubstitutued cyclohexane below, we can say that the methyl group is cis to the ethyl group, and trans to the chlorine. We can also say that the ethyl group is trans to the chlorine. We cannot, however, designate the entire molecule as a cis or trans isomer.

William Reusch, Professor Emeritus (Michigan State U.), Virtual Textbook of Organic Chemistry

- John D. Robert and Marjorie C. Caserio (1977) Basic Principles of Organic Chemistry, second edition. W. A. Benjamin, Inc. , Menlo Park, CA. ISBN 0-8053-8329-8. This content is copyrighted under the following conditions, "You are granted permission for individual, educational, research and non-commercial reproduction, distribution, display and performance of this work in any format."