11.5: Charles’s Law- Volume and Temperature

- Page ID

- 47533

- Learn and apply Charles's Law.

Everybody enjoys the smell and taste of freshly-baked bread. It is light and fluffy as a result of the action of yeast on sugar. The yeast converts the sugar to carbon dioxide, which at high temperatures causes the dough to expand. The end result is an enjoyable treat, especially when covered with melted butter.

Charles's Law

French physicist Jacques Charles (1746-1823) studied the effect of temperature on the volume of a gas at constant pressure. Charles's Law states that the volume of a given mass of gas varies directly with the absolute temperature of the gas when pressure is kept constant. The absolute temperature is temperature measured with the Kelvin scale. The Kelvin scale must be used because zero on the Kelvin scale corresponds to a complete stop of molecular motion.

Mathematically, the direct relationship of Charles's Law can be represented by the following equation:

\[\dfrac{V}{T} = k \nonumber \]

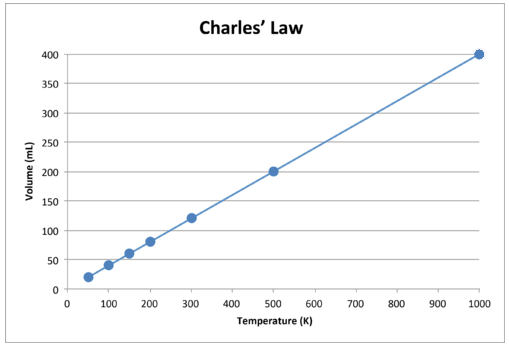

As with Boyle's Law, \(k\) is constant only for a given gas sample. The table below shows temperature and volume data for a set amount of gas at a constant pressure. The third column is the constant for this particular data set and is always equal to the volume divided by the Kelvin temperature.

| Temperature \(\left( \text{K} \right)\) | Volume \(\left( \text{mL} \right)\) | \(\dfrac{V}{T} = k\) \(\left( \dfrac{\text{mL}}{\text{K}} \right)\) |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 20 | 0.40 |

| 100 | 40 | 0.40 |

| 150 | 60 | 0.40 |

| 200 | 80 | 0.40 |

| 300 | 120 | 0.40 |

| 500 | 200 | 0.40 |

| 1000 | 400 | 0.40 |

When this data is graphed, the result is a straight line, indicative of a direct relationship, shown in the figure below.

Notice that the line goes exactly toward the origin, meaning that as the absolute temperature of the gas approaches zero, its volume approaches zero. However, when a gas is brought to extremely cold temperatures, its molecules would eventually condense into the liquid state before reaching absolute zero. The temperature at which this change into the liquid state occurs varies for different gases.

Charles's Law can also be used to compare changing conditions for a gas. Now we use \(V_1\) and \(T_1\) to stand for the initial volume and temperature of a gas, while \(V_2\) and \(T_2\) stand for the final volume and temperature. The mathematical relationship of Charles's Law becomes:

\[\dfrac{V_1}{T_1} = \dfrac{V_2}{T_2} \nonumber \]

This equation can be used to calculate any one of the four quantities if the other three are known. The direct relationship will only hold if the temperatures are expressed in Kelvin. Temperatures in Celsius will not work. Recall the relationship that \(\text{K} = \: ^\text{o} \text{C} + 273\).

A balloon is filled to a volume of \(2.20 \: \text{L}\) at a temperature of \(22^\text{o} \text{C}\). The balloon is then heated to a temperature of \(71^\text{o} \text{C}\). Find the new volume of the balloon.

Solution

| Steps for Problem Solving | |

|---|---|

| Identify the "given" information and what the problem is asking you to "find." |

Given: \(V_1 = 2.20 \: \text{L}\) and \(T_1 = 22^\text{o} \text{C} = 295 \: \text{K}\) \(T_2 = 71^\text{o} \text{C} = 344 \: \text{K}\) Find: V2 = ? L |

| List other known quantities. | The temperatures have first been converted to Kelvin. |

| Plan the problem. |

First, rearrange the equation algebraically to solve for \(V_2\). \[V_2 = \dfrac{V_1 \times T_2}{T_1} \nonumber \] |

| Cancel units and calculate. |

Now substitute the known quantities into the equation and solve. \[V_2 = \dfrac{2.20 \: \text{L} \times 344 \: \cancel{\text{K}}}{295 \: \cancel{\text{K}}} = 2.57 \: \text{L} \nonumber \] |

| Think about your result. | The volume increases as the temperature increases. The result has three significant figures. |

If V1 = 3.77 L and T1 = 255 K, what is V2 if T2 = 123 K?

- Answer

-

1.82 L

A sample of a gas has an initial volume of 34.8 L and an initial temperature of −67°C. What must be the temperature of the gas for its volume to be 25.0 L?

Solution

| Steps for Problem Solving | |

|---|---|

| Identify the "given" information and what the problem is asking you to "find." |

Given: Given:T1 = -27oC and V1 = 34.8 L V2 = 25.0 L Find: T2 = ? K |

| List other known quantities. | K = -27oC + 273 |

| Plan the problem. |

1. Convert the initial temperature to Kelvin 2. Rearrange the equation algebraically to solve for \(T_2\). \[T_2 = \dfrac{V_2 \times T_1}{V_1} \nonumber \] |

| Cancel units and calculate. |

1. −67°C + 273 = 206 K 2. Substitute the known quantities into the equation and solve. \[T_2 = \dfrac{25.0 \: \cancel{\text{L}} \times 206 \: \text{K}}{34.8 \: \cancel{\text{L}}} = 148 \: \text{K} \nonumber \] |

| Think about your result. | This is also equal to −125°C. As temperature decreases, volume decreases—which it does in this example. |

If V1 = 623 mL, T1 = 255°C, and V2 = 277 mL, what is T2?

- Answer

-

235 K, or −38°C

Summary

- Charles’s Law relates the volume and temperature of a gas at constant pressure and amount.