1.5: Collisions and Concentration

- Page ID

- 189836

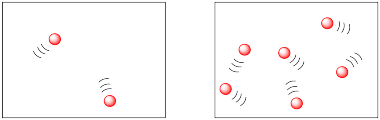

We know that in order for two molecules to react with each other, they must first contact each other. We think of that contact as a "collision". The more mobile the molecules are, the more likely they are to collide. Also, the closer the molecules are together, the more likely they are to collide.

In the following drawings, the molecules are closer together in the picture on the right than they are in the picture on the left. The molecules are more likely to collide and react in the picture on the right.

We might describe the two drawing above in terms of population density. Both drawings appear to offer the same amount of space, but they have different amounts of molecules in them.

The difference is a lot like the difference between human population densities in various locations around the world. Some places, such as Mexico City or Tokyo, are very crowded; they have high population densities. Some places, such as the Australian Outback or the Canadian Arctic, have low population densities.

In which location do you think you are likely to bump into another person: the Upper East Side of New York City or 75 degrees north, 45 degrees west, Greenland?

- Answer

-

Upper East Side. Lots more people per square foot.

Rank the following places in terms of population density (the number of people per square kilometer).

- Russia: pop. 143 million; area 17 million km2

- Bahrain: pop. 1.2 million; area 750 km2

- Argentina: pop. 41 million; area 2.7 million km2

- China: pop. 1.3 billion; area 9.6 million km2

- Malawi: pop. 15 million; area 118 thousand km2

- Vatican City: pop. 850; area 0.44 km2

- Jamaica: pop. 2.7 million; area 10,990 km2

- Answer a

-

8.41 people km-2

- Answer b

-

1,600 people km-2

- Answer c

-

15.2 people km-2

- Answer d

-

13.5 people km-2

- Answer e

-

12.7 people km-2

- Answer f

-

1,930 people km-2

- Answer g

-

24.6 people km-2

- Answer

-

Rank: Bahrain > Vatican > Jamaica > Argentina > China > Malawi > Russia

Sometimes, a lot of people are living in a small area, and the population density is high. Sometimes, the population is large, but the area is, too. Population density depends on two different factors: the number of people and the area in which they are spread out.

Concentration is the term we use to describe the population density of molecules (and other chemical entities such as atoms or ions). It describes the number of molecules there are, but also how much room, or volume, they have to move around. Thus, whereas a human population density may be described in terms of people per square kilometer, the concentration of a solution may be described in terms of molecules per liter.

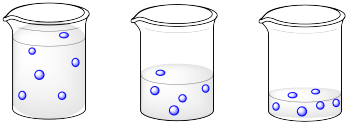

Describe what is happening to the concentrations of the three solutions as you go from left to right.

a)

b)

- Answer a

-

The volume is constant, but the number of molecules is increasing. The concentration is increasing.

- Answer b

-

The number of molecules is constant, but the volume is decreasing. The concentration is increasing.

In the cases above, describe what would happen to rates of collisions between molecules as you go from right to left in the drawings.

- Answer

-

In both cases, the molecules are becoming more densely packed. Collisions would become more frequent as we go from left to right.

a) In the following drawings, state what is happeing to the concentration of molecules of each type as you go from left to right.

b) Explain what would happen to the rate of collisions between red molecules and blue molecules as you move from left to right.

c) How would your answer about rates change if the situation here were reversed: if the number of blue molecules stayed the same and the number of red molecules increased?

d) How would your answer about rates change if the numbers of both the red and the blue molecules were increasing at the same time?

- Answer a

-

The number of blue molecules is increasing, but the number of red molecules is staying the same.

- Answer b

-

Collisions between red and blue molecules would become more frequent as we go from left to right. The higher density of blue molecules makes collisions more likely.

- Answer c

-

The answer would stay the same.

- Answer d

-

The answer would stay the same qualitatively, but would differ quantitatively. The number of collisions would increase more sharply if the concentrations of both red and blue molecules increased, rather than just one concentration increasing.

We usually don't count individual molecules in a solution. We deal with groups of molecules because it's more convenient. Individual molecules are just too small to work with. In dealing with molecules in bulk, we usually use a unit called a mole, often abbreviated to mol. It's kind of like dealing with eggs by the dozen. Molecules are easier to keep track of by the mole, rather than individually.

- In the following solutions, how many dozen blue molecules are there in each case?

- What is happening to the concentration of the beaker as you go from one beaker to the next? Quantify your answer.

- Answer a

-

A half dozen, a dozen, two dozen.

- Answer b

-

The concentration is doubling as we go left to right from one beaker to the next.

In reality, we don't count molecules or even moles of molecules. When we want to work with a compound, we just weigh it out on the balance. We can then use the known weight of the compound to figure out how many moles we have.

Of course, if we are going to be measuring out molecules by weight, we'll need to know how much each molecule weighs. For example, if we need an equal number of red molecules and blue molecules, and red molecules weigh three times as much as blue molecules, we'll need to weigh out three times as much of the red stuff as the blue stuff.

You are developing a new "extreme sport" amusement park ride. Each ride (for one person) is powered by one mouse and one elephant. You have plenty of elephants to get started, but will need to go and buy some mice.

- If an elephant weighs 6,800 kg, how many grams does it weigh?

- If you have 47,600 kg of elephants, how many rides can you set up?

- If a mouse weighs 25 g, how many g of mice will you need to buy?

- Suppose you decide to get three extra mice (sometimes accidents happen around elephants). What is the total weight of mice you would need, including these extras?

- Answer a

-

The elephant weighs 6,800 kg x 1,000 g/kg = 6,800,000 g = 6.8 x 106 g.

- Answer b

-

We have 47,600 kg x 1 elephant/6,800 kg = 7 elephants. Very lucky.

- Answer c

-

7 mice x 25 g/mouse = 175 g.

- Answer d

-

10 mice x 25 g/mouse = 250 g.

Suppose each of the following beakers contains an equal weight of each kind of molecule. The molecular weight of a blue molecule is 60 g/mol. What is the molecular weight of a red, an orange and a grey molecule?

The weight of a molecule can be determined by adding up the weights of all its atoms. For example, a carbon dioxide molecule has a molecular weight of 44 amu (carbon is 12 amu plus two oxygens at 16 amu apiece). The weight of a mole of carbon dioxide is the same as the molecular weight, but in grams instead of amu. A mole of carbon dioxide is 44 g. In other words, the molecular weight (MW) of carbon is 44 g/mol.

- Answer

-

The weight of 7 blue molecules = the weight of 2 red molecules. 1 red molecule = 7/2 x the weight of a blue molecule. MWred = 3.5 x MWblue = 3.5 x 60 g mol-1 = 210 g mol-1.

The weight of 6 blue molecules = the weight of 6 orange molecules. MWorange = MWblue = 60 g mol-1.

The weight of 6 blue molecules = the weight of 1 grey molecule. MWgrey = 6 x MWblue = 6 x 60 g mol-1 = 360 g mol-1.

How much does a mole of each of the following molecules weigh?

- nitric oxide, NO2

- glucose, C6H12O6

- benzaldehyde, C7H6O

- phosphorus pentoxide, P2O5

- Answer a

-

A mole of material corrsponds to the numerical equivalent of the sum of atomic masses in an molecule, in grams.

atomic masses in NO2: 14 amu (N) + 32 amu (2 x O) = 46 amu. 1 mol of NO2 is 46 g of NO2.

- Answer b

-

180 g

- Answer c

-

106 g

- Answer d

-

142 g

How many moles of each of the following compounds are there in the given weights?

- 3 grams of glucose

- 10 grams of benzaldehyde

- 30 grams of phosphorus pentoxide

- Answer a

-

3 g x 1 mol/180 g = 0.017 mol

- Answer b

-

10 g x 1 mol/106 g = 0.094 mol

- Answer c

-

30 g x 142 mol/g = 0.21 mol

What is the concentration of each of the following solutions (in moles per liter)?

- 5 g of glucose in 50 mL of water

- 11 g of benzaldehyde in 25 mL of THF

- 9 g of menthol (MW 156 g/mol) in 60 mL of DMF

- Answer a

-

5 g x 1 mol/180 g = 0.028 mol; 0.028 mol / 50 mL = 5.6 x 10-4 mol/mL x 1000 mL/L = 0.56 mol L-1.

- Answer b

-

11 g x 1 mol/106 g = 0.104 mol; 0.104 mol / 25 mL = 4.16 x 10-3 mol/mL x 1000 mL/L = 4.2 mol L-1.

- Answer c

-

9 g x 1 mol/156 g = 0.058 mol; 0.058 mol / 60 mL = 9.61 x 10-4 mol/mL x 1000 mL/L = 0.96 mol L-1.