6.4: Enzyme Inhibition

- Page ID

- 189956

Compounds other than substrates can play important roles in interacting with enzymes. There are compounds that can either activate or inhibit enzymes, speeding up their activity or slowing them down, respectively. These compounds can be very important in naturally regulating enzymes in the cell. We can also exploit these compounds as medicines, treating illness by tuning the activity of enzymes until the body is back to normal.

Knowing for sure whether a compound is going to turn an enzyme on or off can get pretty complicated, so we are just going to start with a couple of simple ways in which enzymes can be turned off.

Reversible Inhibitors

There are several different ways in which compounds can inhibit enzymes. The simplest way is simply by taking up space in the active site. If something is blocking the active site, the true substrate can't get in, so the enzyme can't do its job.

To block the active site, the inhibitor must also be a pretty good fit. It must have a similar shape, or in some way be able to interact with amino acid residues in the active site. That means it might not have a shape that is obviously familiar, but must be capable of intermolecular interactions that are similar to those of the substrate in the active site.

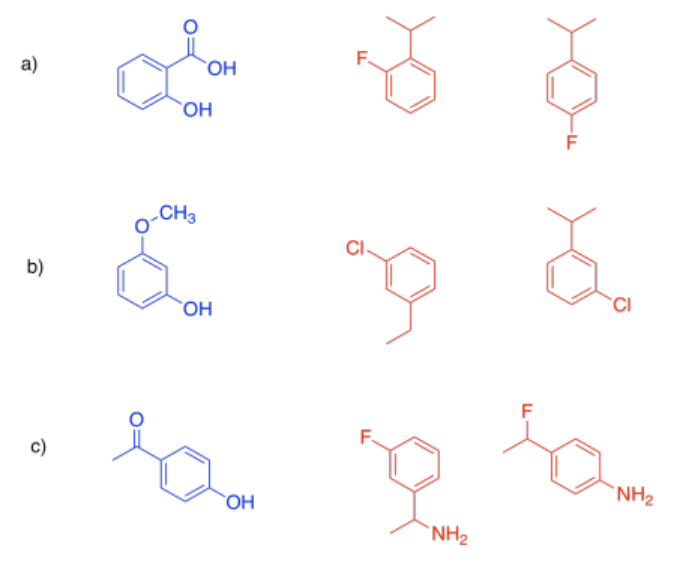

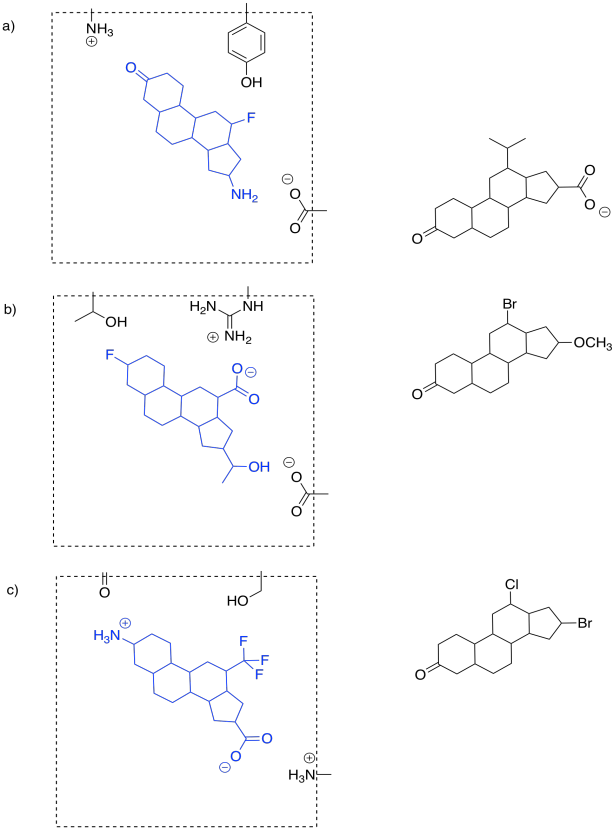

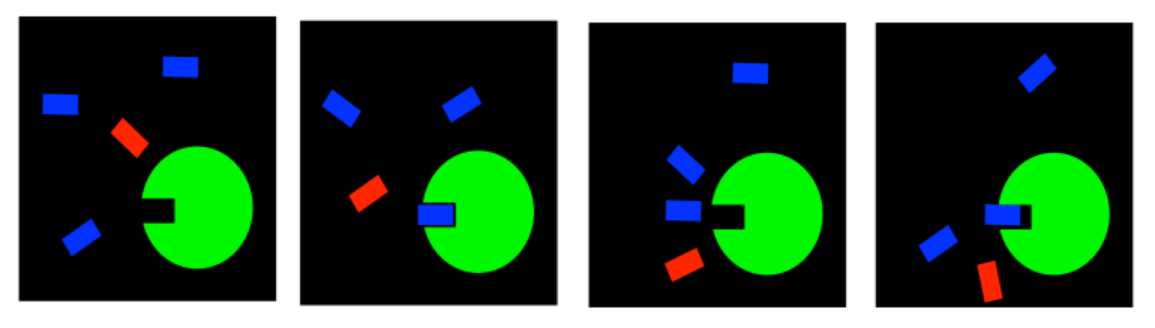

If the substrate is the compound in blue, indicate which of the red compounds would be a better competitive inhibitor.

Answer-

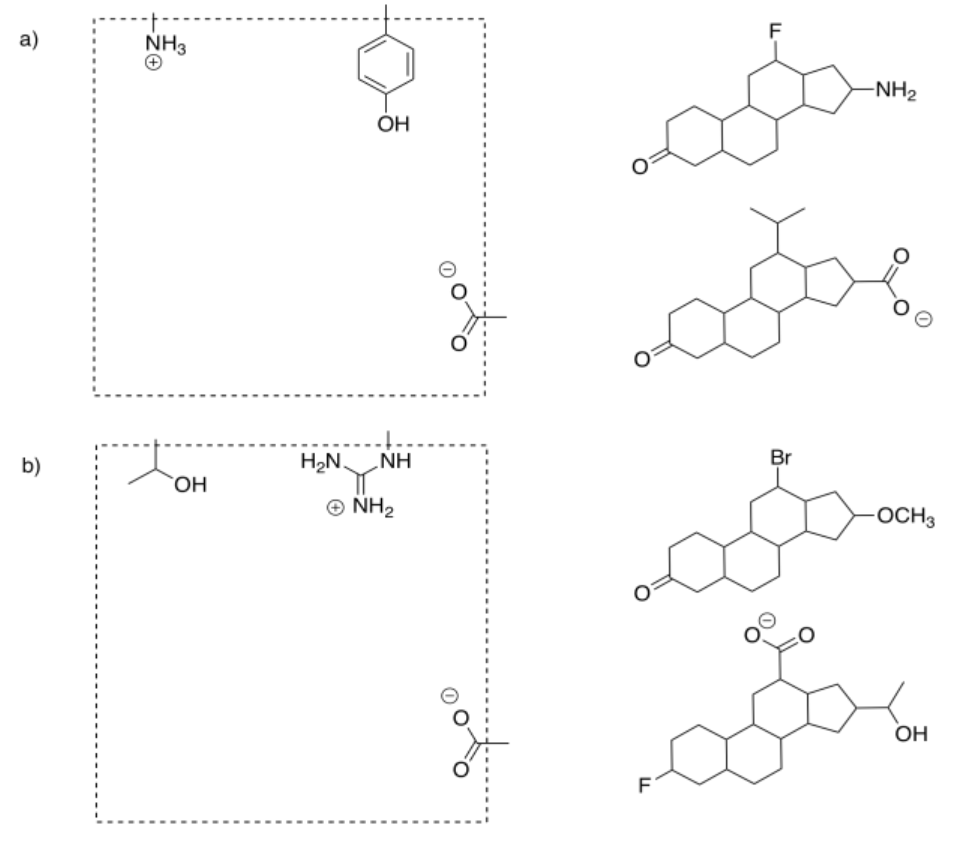

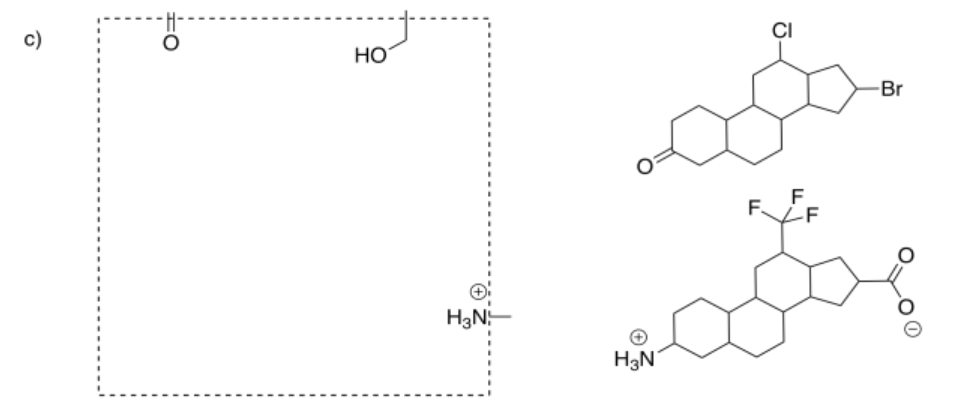

In drug design, the part of the enzyme that binds to the substrate is called the pharmacophore. That's the feature that we will try to exploit in designing an inhibitor. The inhibitor will be designed so that it can also bind to the pharmacophore, either by fitting in terms of shape or by the intermolecular attractions it can supply.

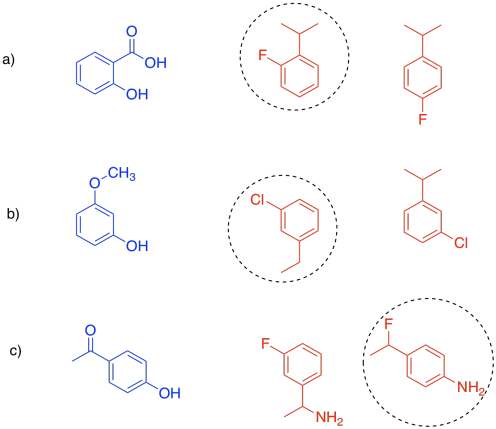

Select the compound that would more efficiently bind to the pharmacophore.

Answer-

Most of the time, if we just want to moderate the effects of an over-active enzyme, we use what is called a reversible inhibitor. We don't want to block the active site of the enzyme permanently; we just want to slow things down, to get things back to normal. After all, the enzyme probably does something useful for us, and we may need it later. So, we use an inhibitor that will slow it down for a while, but whose effects can be reversed.

A competitive inhibitor simply competes with the substrate for the active site. Both the substrate and the inhibitor occupy the same niche, but they can't both sit there at the same time. In general, there is some equilibrium between bound and unbound states. That means that after a while, one molecule wanders back out of the enzyme, and the other one has a chance to enter.

We have mechanisms in the cell that scrub out molecules that shouldn't be there, so eventually, that's what happens to the inhibitor. While the concentration of inhibitor remains high, it can effective compete for the active site of the enzyme. As more and more of it gets removed, the enzyme gets back to its normal levels of activity. Hopefully, by that point, the disease state has eased off.

Irreversible inhibitors

Maybe a disease state is serious enough that we want to shut an enzyme down completely. That might be the case if we are fighting a bacterial or fungal infection, for example; we don't care whether the fungus needs that enzyme later. Causing big problems for the fungus is kind of the whole point at this stage.

In a case like this, we might use what is called an irreversible inhibitor. Once it goes into the enzyme, it never comes back out. It forms a permanent bond, hopefully in a place that blocks the active site or some other important feature of the enzyme.