6: Tetraethyllead - Corporate vs. Government Decisions

- Page ID

- 40255

The alcohol vs.additive struggle for the fuel of the future envisioned by Kettering and the research team at General Motors was not what other industries had in mind.

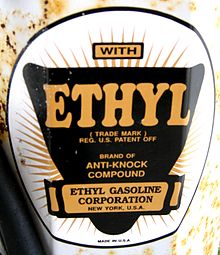

The marriage was a joint venture called the Ethyl Corp. that would sell tetraethlyllead additives for gasoline. It would be produced primarily by GM’s other partner, the DuPont Corp., which had extensive experience handling hazardous chemicals.

Tetraethyllead was indeed hazardous. In 1923 two GM employees died manufacturing it, and fuel Thomas Midgley found he had also come down with lead poisoning and had to take an extended vacation. The DuPont manufacturing process had killed 7 more workers. The public controversy began in October 1924 with the severe poisoning of 50 workers in a Standard Oil refinery in New Jersey just across the bay from New York City. When five of the workers died one day at a time with symptoms described as "violent insanity," the news was carried on the front pages of newspapers around the country. Leaded gasoline was banned in dozens of cities and states and Kettering announced it would be taken off the market voluntarily.

The corporate players in the fuel dilemmas of the first half of the twentieth century are still with us. You might like to see how they characterize themselves today!

- DuPont characterizes itself today as a "science company". The company states, "For nearly 200 years, our core values have remained constant: commitment to safety, health and the environment; integrity and high ethical standards; and treating people with fairness and respect."

- The Ethyl Corporation notes, "Since 1921, Ethyl Corporation has provided additive chemistry solutions to enhance the performance of petroleum products. Our products and services provide the chemistry that makes fuels burn cleaner, engines run smoother and machines last longer."

- Standard Oil, then Standard Oil of New Jersey became Exxon. Exxon and Mobil, once Standard Oil of New York, recently merged, reuniting two segments of John D. Rockefellers original Standard split by Justice nearly 100 years ago. This new Exxon Mobil tells us "Welcome to Exxon Mobil Corporation. Formed by the combination of two high-caliber organizations, Exxon and Mobil, the new company is an industry leader in almost every aspect of the petroleum and petrochemicals business. Even more encouraging is the large array of opportunities for even greater success in the future."

- General Motors reports "Founded in 1908, General Motors has grown into the world's largest automotive corporation and full-line vehicle manufacturer. The company employs more than 388,000 people and partners with over 30,000 supplier companies worldwide. As the largest U.S. exporter of cars and trucks, and having manufacturing operations in 50 countries, General Motors has a global presence in more than 200 countries. Along with designing, manufacturing, and marketing of vehicles, General Motors has substantial interests in digital communications, financial and insurance services, locomotives, and heavy-duty automatic transmissions. GM has more than 260 major subsidiaries, joint ventures, and affiliates around the world."

As the controversy escalated, Midgley and Kettering told the media, fellow scientists and the government that no alternatives existed. “So far as science knows at the present time," Midgley said, "tetraethyllead is the only material available which can bring about these [antiknock] results, which are of vital importance to the continued economic use by the general public of all automotive equipment, and unless a grave and inescapable hazard exists in the manufacture of tetraethyllead, its abandonment cannot be justified.”[i]

At a Public Health Service conference on leaded gasoline in 1925, Kettering said: "We could produce certain [antiknock] results and with the higher gravity gasolines, the aromatic series of compounds, alcohols, etc... [to] get the high compression without the knock, but in the great volume of fuel of the paraffin series [petroleum] we could not do that."[ii] Even though experts like Alice Hamilton of Harvard University insisted that leaded gasoline was dangerous and alternatives were available,[iii] the Public Health Service allowed leaded gasoline to go back on the market in 1926.

GM.’s research into anti-knock fuels had switched gears sometime in 1923 or 1924 because of its partnership with Standard Oil and DuPont. The companies wanted to use tetraethyl lead because if was profitable. Yet to claim that no alternatives existed was clearly misleading, and to ignore public health concerns was nothing less than putting profit ahead of the public interest.

References

- [i] “Radium Derivative $5,000,000 an ounce / Ethyl Gasoline Defended,” New York Times, April 7, 1925, p. 23; Also, Thomas Midgley, Jr., “Tetraethyl Lead Poison Hazards,” Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, Vol. 17, No. 8 August, 1925, p. 827.

- [ii] U.S. Public Health Service, Proceedings of a Conference to Determine Whether or Not There is a Public Health Question in the Manufacture, Distribution or use of Tetraethyl Lead Gasoline, PHS Bulletin No. 158, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Treasury Dept., August 1925), p. 6. (Hereafter cited as PHS Conference). Of course, Kettering originally planned to get alcohols fom outside the paraffin series through grain and cellulose.

- [iii] “U.S. Board Asks Scientists to Find New ‘Doped Gas,’” New York World, May 22, 1925, p. 1.